Review - DOI:10.33594/000000845

Accepted 2 December, 2025 - Published online : 25 January, 2026

1Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Doctoral School, Bukowska 70, 60-812, Poznan, Poland,

2Department of Biology, University of Maryland Global Campus, UMGC in Europe, Poland,

3Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Collegium Maius, Fredry 10, 61-701, Poznan, Poland,

4Food Technology Department, The University of Ibadan, Nigeria,

5Faculty of Pharmacy, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ogun, Nigeria,

6Population Health Sciences Institute, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, NE4 5TG, UK,

7National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Innovation Observatory, Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, NE4 5TG, UK

Background/Aims: Drinking water is essential for maintaining optimal physiological and neurocognitive function, yet its independent role in supporting cognitive health is often overlooked. This study aims to identify influential publications, thematic trends, and underexplored areas, particularly interventions, biomarker use, and potential outcomes of drinking water hydration, which might be developed into guidelines for neuropsychiatric and general populations. Materials: A bibliometric analysis was conducted using Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection databases to identify studies on drinking water hydration, cognition, and mental disorders published between January 1, 2005, and April 26, 2025. Peer-reviewed, English-language studies were included, and non-human animal studies were excluded. Metadata were extracted and analysed using Rayyan for screening and the Bibliometrix R package for bibliometric analysis. Four blinded reviewers applied inclusion/exclusion criteria, resolving disputes through discussion. Thematic trends and gaps were identified by analysing publications, influential works, and emerging themes using Bibliometrix via Biblioshiny through keyword co-occurrence, word cloud analysis, and thematic mapping. Trends were defined as frequent and central themes, while gaps reflected low-frequency and low-density topics, especially those in the emerging/declining quadrant, relative to established research priorities. Results: 14 studies examining the association between drinking water exposure and cognition and mental health outcomes were analysed. In terms of trends, research has primarily focused on the neurocognitive effects of water contaminants, with limited but growing attention to hydration and cognition. A critical gap is the absence of longitudinal, biomarker-informed studies directly linking hydration status to specific mental health outcomes. This gap limits causal inference and intervention development, as thematic and bibliometric analyses reveal fragmented research efforts and a declining trend in scholarly engagement within this interdisciplinary field. Conclusions: Future research should prioritise targeted studies and standardised biomarkers to understand hypothesized links better and inform evidence-based hydration guidelines. Specific recommendations regarding water intake for cognitive or mental health benefits are not available and deserve attention.

It is widely agreed that water is fundamental to human health and essential for maintaining physiological and neurocognitive function [1–3]. However, the specific role of adequate drinking water intake in supporting brain performance and mental well-being remains to be characterized. According to Liska et al. 2019, hydration is the process of maintaining water balance in the body [4]. We therefore define drinking water hydration as the process by which water consumed through drinking plain water contributes to maintaining the body’s fluid balance, supporting physiological and cognitive functions. This definition distinguishes it from total hydration, which may also include water from food and metabolic sources.

Mild dehydration can negatively affect energy levels, cognitive function, and overall health [5, 6]. Body water loss of as little as 1-2% can cause low concentration, memory issues, and physical performance [7–9]. Many psychiatric conditions, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, are characterised by varying degrees of cognitive impairment [10]. While the cognitive effects of hydration status have received considerable attention in general populations, research in population subgroups may also be important.

Water quality differs significantly across sources and can be unsafe because of varying contamination types, particularly microbial risks [11, 12]. Studies also tend to group clean and polluted water together, despite their distinct health effects [12]. The wide variation in individual hydration needs adds complexity to population-level assessments [13]. Cognitive function and mental health presentations vary significantly across age and demographic groups, requiring age- and sex-specific clinical considerations.

Changes in hydration status is an essential concern in psychiatric populations. Several factors contribute to an increased risk of water imbalance. Pharmacological treatments, such as lithium therapy, play a significant role as they induce polydipsia (excessive thirst) and polyuria (frequent urination) due to their impact on renal function [14]. Lithium therapy would work worse if people don't drink water because the medication causes excessive thirst and frequent urination that affects kidney function, making adequate water intake necessary for the treatment to function properly. The term psychogenic polydipsia (PPD), characterised by excessive water intake and increased urine output in the absence of physiological triggers, is frequently observed in individuals with psychiatric disorders [15]. Also, certain antipsychotics may promote hyponatremia by enhancing the secretion of antidiuretic hormone (arginine vasopressin, AVP) or by sensitising renal pathways to its effects [16]. Complex interplay between psychiatric pathology and hydration status, underscores the need for a more systematic exploration of the impact of drinking water in this population. Given these factors also, shouldn't there be strict individualised water intake guidelines rather than encouraging unlimited hydration, especially since maintaining sodium levels between 136-145 mEq/L [17] requires careful fluid balance?

Biomarkers such as plasma osmolality, copeptin, and vasopressin offer promising avenues to study the physiological link between hydration and cognition. High levels of copeptin are associated with low water intake [18, 19]. Copeptin is also a stress biomarker, reflecting the activation of vasopressin in response to stressors [20, 21]. This could directly or indirectly link copeptin to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a key component in stress response [22, 23].

Current drinking water guidelines provided by global health authorities such as the World Health Organisation and European Food Safety Authority do not account for the unique needs of individuals with mental disorders [4, 24, 25]. All these create a pressing need to synthesise the emerging but fragmented literature in this interdisciplinary field. The study by Stookey and Kavouras 2020 highlights a knowledge and evidence gathering gap in drinking water recommendations and impact, and proposes that research explore investigations across disciplines and contexts [26]. Parkinson et al. 2023 found dehydration in one in every four older adults, thus stressing the need for studies aimed at understanding drinking behaviours and evaluating hydration and its interventions [27], as this might impact cognitive function in mental disorders. Similarly, findings from the bibliometric analysis by Masot et al. 2025 highlight the need for more research tailored towards hydration interventions in older adults [28].

This study conducts a bibliometric analysis of global research on the relationship between drinking water hydration and cognition and mental health. This is to check for gaps in the literature about drinking water hydration as distinct from total hydration using biomarkers, and absence of individualised hydration guidelines for mental health patients who face unique risks from medications and disorders that disrupt fluid regulation. Specifically, it aims to identify influential publications, thematic trends, and underexplored areas, especially interventions, biomarker use and potential outcomes of drinking water hydration that can link or align with population-based data to translate into guidelines for both psychiatric and the general populations. While systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide valuable insights into a specific research area, bibliometric analysis applies quantitative methods to offer a broader, more comprehensive understanding of the field's structure, evolution, and emerging trends [29]. It excels at identifying key research and emerging areas, and visualising the intellectual landscape of a discipline [29].

We hypothesise that research and evidence in the intersecting area of drinking water hydration and cognition in mental health is limited, representing "low evidence" rather than "robust evidence." We define "robust evidence" as having sufficient research volume, consistent findings across studies, and well-established theoretical frameworks, while "low evidence" reflects sparse research, inconsistent methodologies, and limited replication of findings. The primary aim is therefore to map the current evidence landscape to determine whether robust evidence exists or if we are dealing with low evidence that requires foundational research development.

Search strategy

The methodology was carefully planned based on our previous study methodology [30], and following the bibliometric reviews of the biomedical literature (BIBLIO) guideline [31]. A comprehensive bibliometric search was conducted using Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) databases, which are widely used in bibliometric research due to their robust and comprehensive metadata and citation indexing [32, 33]. The metadata included publication title, authors, keywords, journal source, publication year, citations, affiliations, and document type. The search strategy and Boolean operators used are provided in Table 1 below.Table 1. Literature database search strategy keywords

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion was limited to articles searched from January 1st 2005, to April 26th, 2025, to capture past and contemporary drinking water hydration and cognitive neuroscience developments. Only peer-reviewed original articles were included. Non-English language restrictions were applied during the search.

Data extraction and synthesis

Metadata were exported from the databases in .bib formats, imported into R programming for cleaning, exported and uploaded to Rayyan (AI-powered systematic review platform) [34], where it was screened using the following inclusion criteria by four blinded reviewers:

This dual AI-human process ensured both efficiency and judgment-based refinement. All non-human animal studies were excluded. To lessen the chance of selection bias, all disputes were resolved through discussions between the reviewers. The final output was imported into the Bibliometrix R package (via RStudio) Biblioshiny [35] for bibliometric analysis. This platform enables detailed quantitative and visual analysis of descriptive statistics, co-authorship and keyword co-occurrence networks, co-citation analyses, thematic clustering, and trend mapping [30]. Analyses included annual scientific production, which quantified yearly publication counts. The trend was defined as a consistent increase or decrease in publication volume over time. Citation analysis identified influential studies based on total citation counts. Source analysis examined the distribution of publications across journals to evaluate the concentration or fragmentation of research within and across disciplines. Keyword co-occurrence analysis and word clouds were used to visualize frequently occurring terms and thematic clusters, helping to reveal dominant research areas and underexplored topics. Word clouds highlighted both prevailing and neglected terms. Clustering algorithms categorized research into four categories based on how important and developed they are. Motor themes are both important and well-studied. Basic themes are important, but not yet fully developed. Niche themes are well-studied but not strongly connected to other topics. Emerging or declining themes are less developed and less connected, and may represent new or fading areas of research. Collaboration and authorship network analysis mapped co-authorship across countries to assess the geographic distribution of research efforts and the extent of cross-border collaboration. Gaps in the literature were identified based on the low frequency or absence of key terms (e.g., hydration biomarkers, mental disorders beyond depression), limited representation of vulnerable populations (e.g., older adults), and a lack of sustained publication or citation trends over time. Journal analysis was conducted to understand disciplinary silos and determine whether research output is concentrated or scattered. Although funding source analysis could have offered valuable context regarding research drivers and potential biases, this information was not consistently available in the metadata and was therefore not included.

The quality of evidence from the included studies was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria [36]. This method provided a structured framework for evaluating the certainty of evidence across key domains, including study design, risk of bias, consistency of results, directness of evidence, precision of estimates, and potential publication bias.A flowchart of the study methodology following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is provided in Fig. 1.

Supplementary Table S1 summarises the characteristics and key findings of the 14 studies included in this evi-dence synthesis. Each study was evaluated for the strength of inference, study design, population, interventions or exposures, outcomes, and any identified biological biomarkers. Of the 14 included studies, 1 study was rated as having a high strength of inference, 6 studies were rated as moderate to moderate-high, 4 studies were rated as low to moderate, and 3 studies were rated as very low. This distribution highlights a predominance of mod-erate-quality evidence, with only a single study providing high-confidence results.

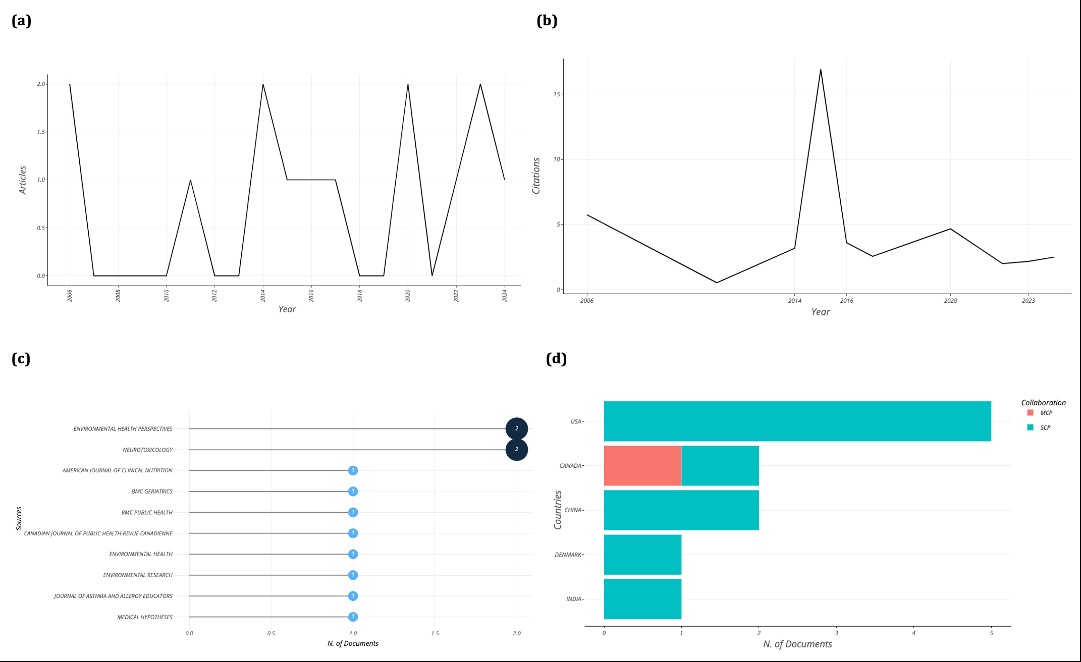

Fig. 2 shows a research metrics dashboard showing statistics from 2006 to 2024 after screening based on our exclusion criteria. Limited research output was found on drinking water and cognitive function and mental health over the 20-year period (2006-2024), with only 14 documents identified from 12 sources. These studies were authored by 88 researchers with high collaborative patterns (7.14% international co-authorship and 6.36 co-authors per document). The field showed a declining annual growth rate of -3.78%, indicating decreasing research interest over time. Documents had an average age of 8.5 years and received substantial attention, averaging 45.79 citations 2

The article publication counts from 2006 to 2024 exhibit notable fluctuations (Fig. 3a), spread over two decades and not clustered in a single period. An initial high count in 2006 is followed by a rapid decline, reaching zero by 2007. Although the count briefly returns to near-zero levels following these early gains, a small peak emerges in 2013, before gradually tapering off through 2014–2016. Another period of low output is observed from 2017 to 2018. However, the data then indicate renewed activity with a marked spike in 2019 and a sudden rise in 2021. After a dip in 2022, the trend again suggests heightened output, culminating in a pronounced peak in 2023 and a slight decline into 2024.

Fig. 3b shows the average citation over time with a notable spike in 2014, reaching its peak value around 2015. Fig. 3c shows the journals that publish papers on this topic, the majority of which were journals from the USA (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3. Bibliometric performance and collaboration trends of publications. (a) Publication over time, (b) Citation over time, (c) Top ten most publishing journals, (d) Corresponding author countries and collaboration. MCP – Multiple Country Publication, SCP – Single Country Publication. N of Documents – Number of documents.

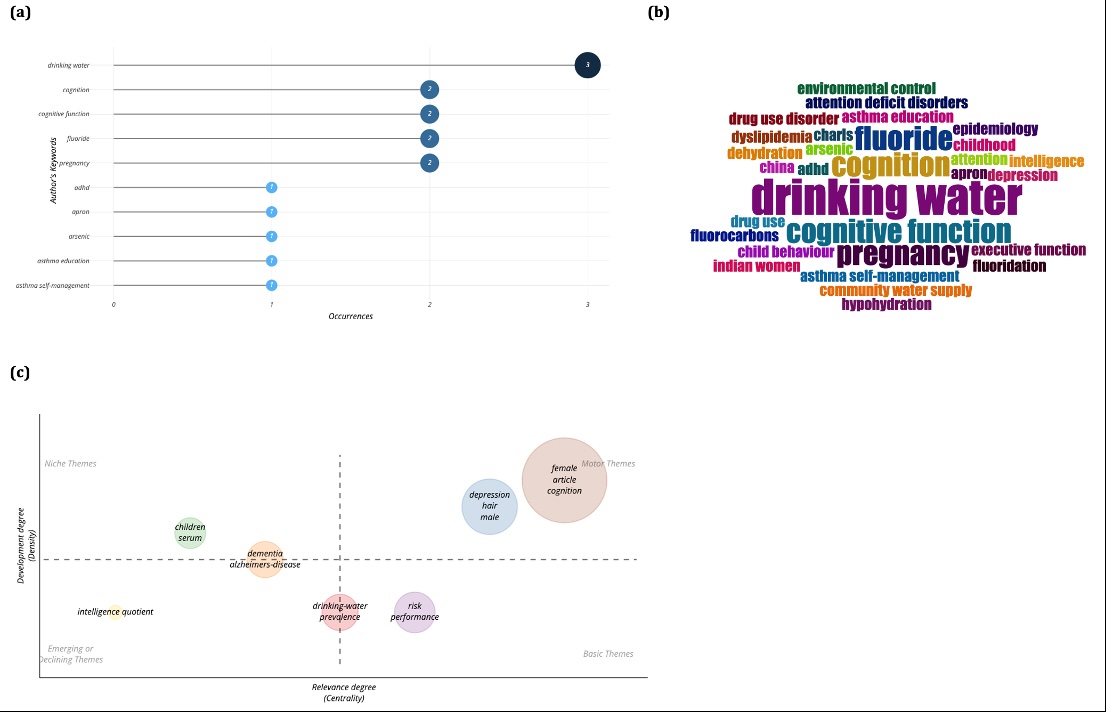

Fig. 4a shows the ten most frequent author keywords. "Drinking water" is the most prevalent keyword (three occurrences), followed by "cognition," "cognitive function," "fluoride," and "pregnancy," with two occurrences each. The remaining keywords appear once.

Fig. 4. Keyword and thematic analysis of research trends (a) Most frequent author keywords (b) Word cloud showing key research terms (c) Thematic map of research topics.

The word cloud (Fig. 4b) reveals prominent themes centred around "drinking water" and "cognition" as the largest terms, indicating their central importance in this study. Secondary themes include "fluoride," "cognitive function," and "cognitive function." Health-related terms such as "dyslipidemia," "asthma," and "attention deficit disorders" appear as secondary topics.

The thematic map (Fig. 4c) categorises research topics into distinct quadrants defined by their relevance (centrality) and developmental maturity (density). Motor themes identified were "female”, “cognition", and "depression," situated in the top-right quadrant, indicating well-established and highly influential areas. "Intelligence quotient," located in the bottom-left quadrant, is an emerging or possibly declining theme. The keywords “female,” “article,” and “cognition” together suggest that a substantial portion of the literature focuses on cognitive outcomes in female populations, often reported across diverse empirical studies (“article”). "Children” and “serum" were identified as a niche topic. "Dementia" and "alzheimer’s-disease" were identified as borderline between emergent and niche topics.

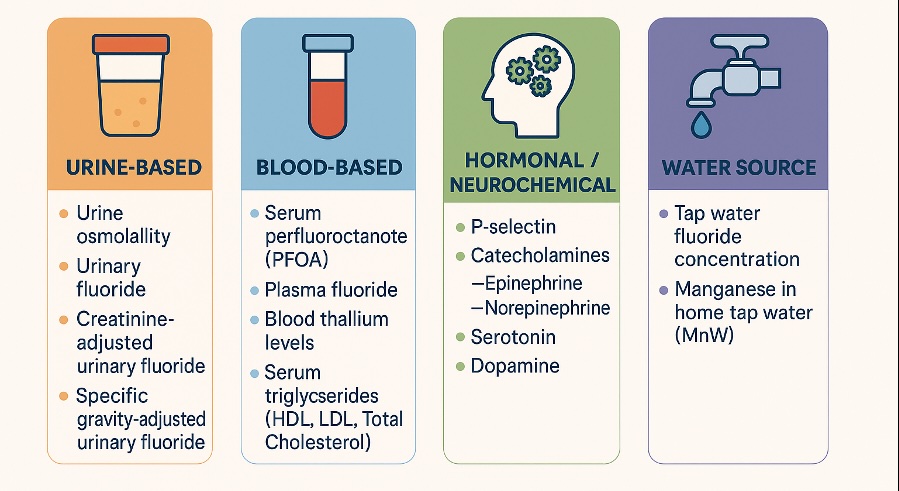

Fig. 5 illustrates the distribution of identified biomarkers from our analysis of 14 studies by type.

Fig. 5. Diversity of biomarkers used in drinking water hydration and cognition from our 14 analyzed studies.

This bibliometric analysis synthesised evidence from 14 studies examining the association between drinking water exposure and cognitive or mental health outcomes. The review reveals a low volume of empirical research at the intersection of drinking water, cognition, and mental health, suggesting a need for further investigation.

Bibliometric analysis reveals that research on the interplay between drinking water hydration and cognitive or mental health outcomes is lacking. Over the 2006–2024 timespan, only 14 documents across 12 sources were identified, reflecting a negative annual growth rate of -3.78%. This declining trend suggests that despite growing public health interest in hydration and mental health, scholarly output in this niche remains limited and inconsistent. Notably, publications not sustained, indicate a lack of continuous engagement or dedicated research programs in this domain.

The citation trajectory from 2006 to 2024 displays considerable variability, with a peak around 2015 reaching around 17 citations, indicating a landmark publication or a particularly influential study temporarily elevated the field’s visibility. The lack of sustained growth in citations suggests that these insights were not consistently built upon in later works.

Source analysis reveals that research in this domain is dispersed across various journals, with only Environmental Health Perspectives and Neurotoxicology contributing more than one publication each. This dispersion into diverse, domain-specific journals, such as BMC Geriatrics, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, and Environmental Research, highlights the interdisciplinary nature of the topic, which intersects nutrition, toxicology, geriatrics, public health, and environmental sciences. However, this diversity may also fragment the research community, making it harder for researchers to track developments, synthesize findings, or build coherent bodies of evidence.

The quality of evidence among the included 14 studies varied considerably, influencing the confidence in their applicability for recommendation development. High-quality evidence, primarily from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and well-conducted prospective cohort studies, provides the highest certainty and is most suitable for informing strong, evidence-based recommendations regarding hydration and cognitive or mental health outcomes. Moderate-quality evidence, often derived from large-scale cohort studies and nationally representative cross-sectional surveys, offers moderate confidence in the estimated effects. Such studies are valuable for identifying population trends, supporting subgroup analyses, and contributing to conditional recommendations or refinement of existing guidelines. Low to very low-quality evidence, typically from cross-sectional designs with small samples or high risk of bias, carries limited certainty. While insufficient for forming recommendations, these studies are useful for hypothesis generation and for detecting early signals that may warrant further investigation through higher-quality designs.

A recurring theme across the reviewed studies was the detrimental effect of drinking water contaminants on neurocognitive development and mental health. Several studies reported significant associations between exposure to fluoride, perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), manganese (Mn), arsenic, tetrachloroethylene (PCE), and thallium and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children and adults. For instance, prenatal and early-life exposure to fluoridated water was linked to poorer inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility in girls [42], while Mn exposure in early childhood was associated with an increased risk of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms [43, 48]. Arsenic exposure among rural Indian women was linked to a higher prevalence of neurobehavioral symptoms and depression [47]. These findings are consistent with the broader environmental health literature identifying neurotoxicants such as heavy metals and certain pesticides as key contributors to cognitive deficits and behavioural disorders [51, 52]. Notably, some effects were sex-specific, with girls demonstrating heightened vulnerability in studies involving PFOA [41] and fluoride [42], potentially reflecting sex-based neuroendocrine or metabolic differences during development. While causal inferences remain limited due to the observational nature of most studies, the cumulative evidence supports the hypothesis that chronic exposure to even low-to-moderate levels of neurotoxicants in drinking water can disrupt neurodevelopmental trajectories. Any recommendation seeking to benefit drinking water for mental health outcomes would need to explicitly assume drinking water is clean and safe.

We observed that only a few studies addressed both drinking water and hydration directly. One experimental study [38] demonstrated that mild dehydration (<1% body mass loss) impairs memory and attention in young adults, with water consumption reversing these effects. This finding corroborates prior work indicating that dehydration impacts brain function via changes in plasma osmolality, blood volume, and neurotransmitter balance [53–57].

In our 14 analysed publications, biomarkers were used in just over half of the studies to quantify exposure (e.g., plasma fluoride, blood thallium, urinary osmolality) or biological response (e.g., serum lipids, catecholamines, serotonin). These can form part of the compilation of biomarkers to be included in guidelines for studying drinking water hydration in relation to cognition and mental health. For example, catecholamines released in response to stress and linked to cognitive changes regulate heart rate, blood pressure, and alertness [58–60]. Investigating whether drinking water hydration correlates with lower catecholamine levels may provide insight into its potential role in stress reduction and the prevention or management of stress-related mental disorders.

The United States led research output, followed by Canada, China, Denmark, and India. This may be influenced by our exclusion of non-English language documents in the search strategy, which could underrepresent research from non-English speaking countries. The dominance of single-country publications indicates a need for more cross-border collaborations to enrich the research diversity and applicability of findings. Keyword frequency analysis identifies "drinking water" as the most recurrent term, followed by "cognition," "cognitive function". Other terms such as "depression" and "adhd" appear less frequently. This distribution suggests a primary focus on general cognitive functions and water quality parameters, with limited exploration into specific mental health conditions. The narrow thematic scope indicates potential research gaps, particularly concerning the nuanced impacts of hydration on various mental health outcomes.

While themes such as "drinking-water prevalence" and mental health conditions like "depression" and "dementia" are represented, the interconnection with hydration status remains underexplored. Researchers consistently include the term "hydration" to improve study visibility and advance understanding of how optimal hydration influences cognitive performance and mental health, especially in mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. Many water quality studies do not incorporate hydration status or its biomarkers, potentially overlooking hydration’s beneficial or modifying effects on cognitive and mental health. Hydration studies may also focus primarily on fluid intake or hydration biomarkers without thoroughly considering water quality factors such as contaminants or mineral content. This oversight can limit understanding of how water quality might interact with hydration status to affect cognitive and mental health outcomes. Integrating both hydration measures and water quality assessments in future research would provide a more comprehensive picture of their combined influence on brain health. If adequate hydration helps prevent or slow cognitive decline, then fear of drinking water, driven by conflicting messages about contaminants, poses a serious concern.

The implication of low evidence and empirical research at the intersection of drinking water hydration, cognitive function, and mental health is that health authorities cannot recommend drinking water for mental health. Future research is crucial to inform the development of targeted and evidence-based hydration guidelines that address the unique needs of older adults and individuals with mental health challenges.

Although several studies involved vulnerable populations, such as children, older adults, and maternal-child pairs, none presented stratified analyses that could inform hydration guidance tailored to these groups. The findings are not analysed in a way that could guide subgroup-specific recommendations. Future research should adopt stratified study designs and explicitly consider the hydration needs of diverse populations to ensure recommendations are evidence-based and inclusive.

We propose the following recommendations for researchers, public health experts, and policymakers.

For Researchers:

For Public Health Experts:

For Policymakers:

Although this paper lays a robust foundation for future research and guidelines development, we must acknowledge certain limitations. We may have missed relevant studies due to the reliance on the Web of Science and Scopus databases only, potentially overlooking publications indexed in other databases or the grey literature. The search strategy, while designed to balance precision and relevance, may have missed studies using alternative phrasings for drinking water, such as “plain water,” “tap water,” “bottled water,” or “water to drink”, due to variability in terminology and indexing practices across disciplines. This presents a known limitation in bibliometric searches and may have constrained the breadth of included literature. The quality and scope of the included publications also limit the study's findings. The analysis may have been affected by inconsistent categorising of articles as reviews, original research, or others by different journals, potentially influencing the interpretation of the evidence base. Although detailed study characteristics were extracted from the final selected studies to enhance interpretation and applied the GRADE tool, we did not perform other formal critical appraisal using standardised risk-of-bias tools, as this was outside the primary scope of this bibliometric study.

Most research on drinking water centres on contaminants' neurocognitive effects, with a limited focus on hydration. The lack of biomarker-based longitudinal studies linking hydration to cognition and mental health underscores a major gap. Addressing it requires well-designed cohort studies or randomised trials using validated biomarkers to clarify the neurocognitive effects of hydration over time. The limited empirical evidence observed in this study raises the question: if hydration significantly impacts cognition, why then is drinking water not strongly prioritised in investigations?

OE acknowledge the Poznan University of Medical Sciences for their support in promoting research and internationalisation. OE is a participant of the STER Internationalisation of Doctoral Schools Programme from NAWA Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange No. PPI/STE/2020/1/00014/DEC/02.

OE participated in the EU-funded Erasmus+ Blended Intensive Program in December 2024 at Paracelsus Medical University in Salzburg, Austria, and wishes to thank the organisers and facilitators for the knowledge and skills that helped conceptualise this work.

Author Contributions: OE was responsible for all aspects of the project, including conceptualisation, research design and implementation, data analysis and interpretation, writing and reviewing, manuscript preparation, supervision, project management, and primary responsibility for the final content. COU and VB provided essential expertise in methodology development, data analysis and interpretation, software usage, writing, reviewing, and manuscript preparation. FON contributed to software usage and manuscript preparation. OAA contributed to writing and manuscript preparation.

Funding Sources

No external funding was utilised for this study or manuscript preparation.

Statement of Ethics

Not applicable because a bibliometric study uses only publicly accessible secondary data and does not involve human participants, identifiable personal information, or any intervention.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated are contained within the manuscript.

The authors have no Disclosure Statement to declare.The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.No competing interests related to the methods or materials used in this study.