Review - DOI:10.33594/000000842

Accepted 1 December 2025 - Published online 15 January 2026

1Research Program for Musculoskeletal Imaging, Center for Anatomy & Cell Biology, Paracelsus Medical University (PMU), Salzburg, Austria;

2Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Arthritis and Rehabilitation (LBIAR), Paracelsus Medical University (PMU), Salzburg, Austria;

3Chondrometrics GmbH, Freilassing, Germany;

4Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College London, London, UK;

5Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Boise State University, Boise, ID, USA

MRI has transformed medical imaging and research by enabling detailed 3D visualization of soft tissue anatomy. But it also provides insight into biophysical, histological, and mechanical properties via quantitative MRI relaxometry (qMRI). Cartilage transverse relaxation time (T2) has emerged as probably the most robust non-invasive marker of cartilage composition and histological assessment, and of cartilage mechanical properties. As such, T2 mapping may represent a powerful tool in cartilage research, epidemiological studies, and osteoarthritis clinical trials. Our review comprises 19 original articles and 14 abstracts published over 12 years (2014-2025). It begins with technically and anatomically orientated studies, expanding to observational and interventional research in idiopathic and post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Key technical advancements include a shift from slow 2D multi-echo spin-echo (MESE) to rapid 3D high-resolution qDESS T2-imaging, an advance from manual to fully automated, AI-based segmentation, the adoption of laminar, subregional, and location-independent T2-analysis methods, and others. The review ends with a concluding paragraph, encompassing current goals and future directions of cartilage T2 imaging in research, clinical trials, and clinical practice, and emerging novel projects. This selfie review aims to summarize the progress in cartilage T2 imaging, from the method development and technical implementation initially supported by the PMU Research Fund, to its application in clinical studies and trials, supported by National and International funding bodies, such as the European Union (EU). We reviewed original articles and conference abstracts on cartilage T2 that involve contributions from our group, categorizing them by funding source and summarizing their key findings.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has revolutionized medical imaging, offering detailed, non-invasive insights into the human body. Unlike X-rays or CT scans, MRI does not rely on ionizing radiation but instead utilizes powerful magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses to manipulate the intrinsic magnetic properties of hydrogen nuclei in water and fat molecules. This interaction generates signals that can be translated into high-resolution images of soft tissues, organs, and other structures. Paul Lauterbur and Sir Peter Mansfield pioneered MRI in the 1970s with their groundbreaking work on spatial localization and MRI sequences earning them the Nobel Prize in Physiology & Medicine in 2003 [1].Whole-body hydration translates to cell hydration and vice versa. Drinking water equilibrates throughout the body water pool within two hours [1]. Cell hydration, which is under tight homeostatic control, determines if body water is retained, lost, or produced by metabolism [2-10]. Although cell hydration is well known to strongly modify cell metabolism [4, 5, 11], corresponding relationships at the whole-body level are less well understood. Causal effects of chronic whole-body hydration on metabolic syndrome-related disorders and mortality are hypothesized based on cell hydration effects [12-16], but remain to be confirmed.

MRI has transformed both clinical diagnostics and research by enabling the visualization of internal anatomy with unprecedented resolution and contrast and is particularly suited for musculoskeletal conditions [2]. Beyond static imaging, MRI techniques now also include dynamic studies, functional assessments, and molecular imaging, opening new frontiers for early disease detection, monitoring of treatment, and what is called “personalized” or “precision” medicine” [3] .

Within the realm of MRI, relaxometry refers to the quantitative measurement of tissue relaxation times—specifically T1, T2, and T2*, measures that reflect how quickly excited protons return to thermal equilibrium after being “disturbed” by a radiofrequency pulse [4]. T1 represents the longitudinal or spin-lattice relaxation, and describes the recovery of magnetization along the direction of the external magnetic field (the longitudinal axis). T1 is impacted by tissue properties such as fat and water content and is often used to differentiate between various tissue types. T2, in contrast, relates to the transverse or spin-spin relaxation time, and describes the decay of magnetization in the plane perpendicular to the external magnetic field (the transverse plane). The radiofrequency signal detected in MRI is directly proportional to magnetization in the transverse plane, and thus the signal in MRI also inherently decays with time constant T2 [4]. The reason for the numbering (T1=longitudinal, T2=transverse) is historical: T1 was researched and published first and T2 later, when researchers realized that interactions between neighboring spins caused an additional signal loss, before longitudinal recovery was complete. However, the number (1 or 2) does not designate “importance”.

This review will focus on measurements of cartilage T2 relaxation times. As mentioned, T2 describes the decay of transverse magnetization due to interactions between neighboring protons, making it sensitive to tissue composition and microstructure [4]. T2 mapping is a specific relaxometry technique that generates maps of T2 values across the tissue, making it possible to detect subtle biochemical and structural changes before they become apparent on conventional MRI sequences (or other imaging techniques, such as computed tomography and radiographs). Thus, T2 relaxometry by quantitative MRI (qMRI) can provide a powerful tool for early diagnosis and monitoring of cartilage disease and its progression [4]. T2* is another relaxometry parameter related to T2, but it incorporates additional signal loss caused by local magnetic field inhomogeneity. While T2 reflects intrinsic tissue properties only, T2* is also sensitive to variations in magnetic susceptibility, making it useful in detecting calcifications, iron deposition, and hemorrhage.

The measurement of articular cartilage tissue T2 was motivated by efforts to non-invasively assess synovial joint health and integrity, particularly in the context of osteoarthritis (OA) research [5] (Fig. 1). OA is the most common form of arthritis and affects more than 500 million people worldwide; it causes medical expenditures on the order of 2.5% of the gross domestic product [6]. It is a serious and highly debilitating whole-organ, multi-tissue disease [7], and so far no disease modifying OA drug (DMOAD) with an effect on the natural course of the disease and its structural pathology has been approved. The knee is the site most commonly affected by OA, and within the knee, the femorotibial joint is the one that is clinically most relevant.

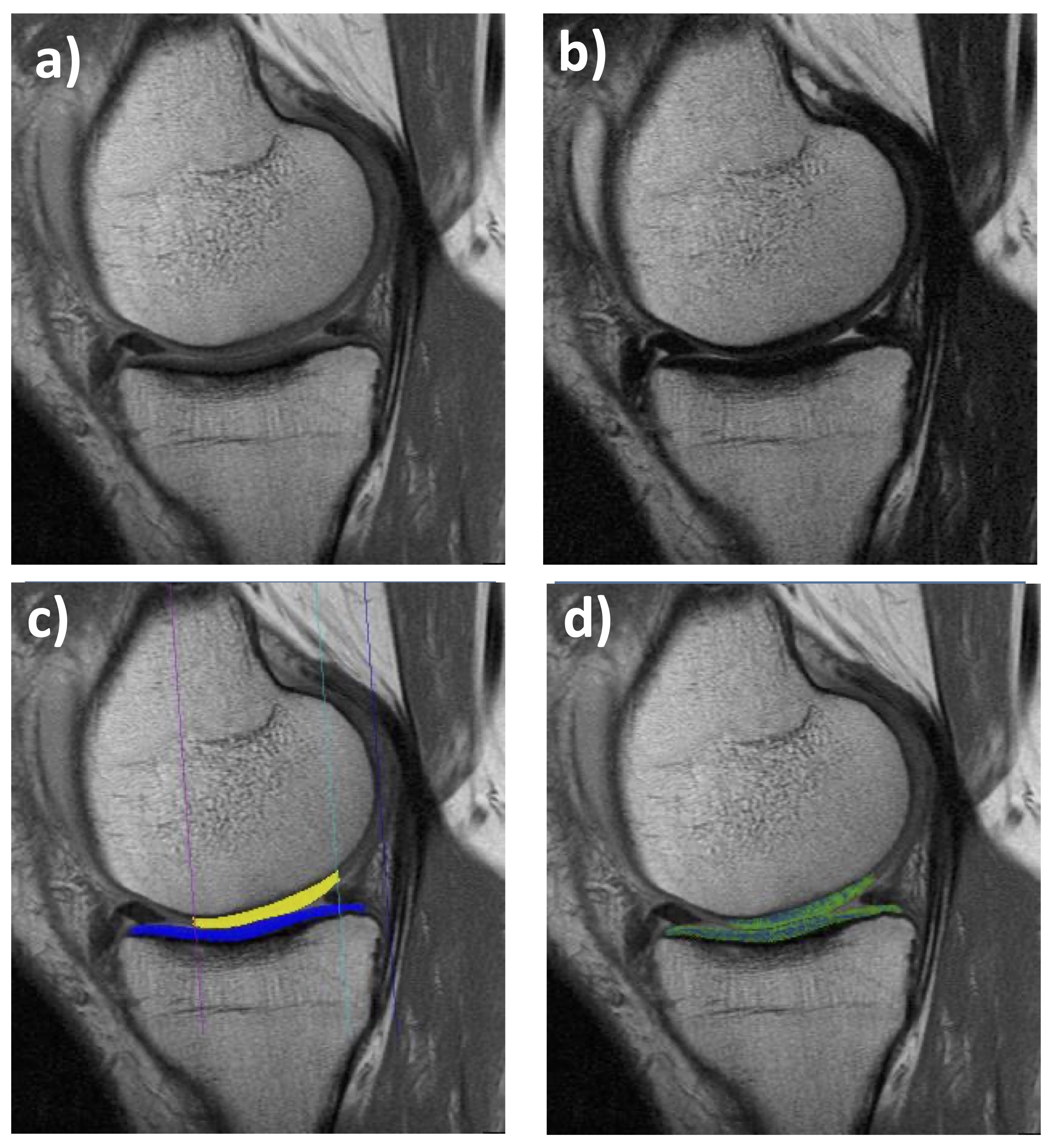

Figure 1. Sagittal multiple-echo spin-echo (MESE) MRI of the medial femorotibial compartment (MFTC): a) Shortest echo (10 ms); b) Longest echo (70 ms); c) Cartilage segmentation of the medial tibia (MT) and lateral tibia (LT); d)T2 map (only cartilage T2 is shown, no other structures)

Articular cartilage is a highly organized and functional tissue composed of a high proportion of water, and a matrix consisting of macromolecules, such as collagen fibers and proteoglycans [8, 9].. These large molecules are designed to maintain the fluid within the matrix, making use of its ability to undergo hydrostatic pressurization, to provide an even distribution of pressure from one (subchondral) bone to the other [10, 11], as well as superior lubrication properties [12, 13].

Structural pathology of cartilage is a hallmark of OA. T2 values in cartilage are primarily influenced by water content and collagen fiber orientation, and much less by proteoglycans (for other MRI techniques to interrogate these, see below). Increased T2 relaxation time has been reported to reflect early biochemical changes such as collagen matrix disruption and increased water mobility, before gross morphological defects or actual quantitative tissue loss are visible [5, 14], and was shown to correlate with histological grading [15, 16] and cartilage mechanical properties [17]. T2 has thus garnered interest as an imaging biomarker for detecting and monitoring “early” stages of OA (4, 18–21) at which therapeutic intervention is potentially more successful than at more advanced ones. T2 mapping of articular cartilage therefore has become a valuable biomarker in musculoskeletal imaging, offering insights into the early stages of cartilage structural modification, before tissue loss is detected by alternate MRI methodologies or on radiographs; the clinical trial standard before the advent of MRI[22].

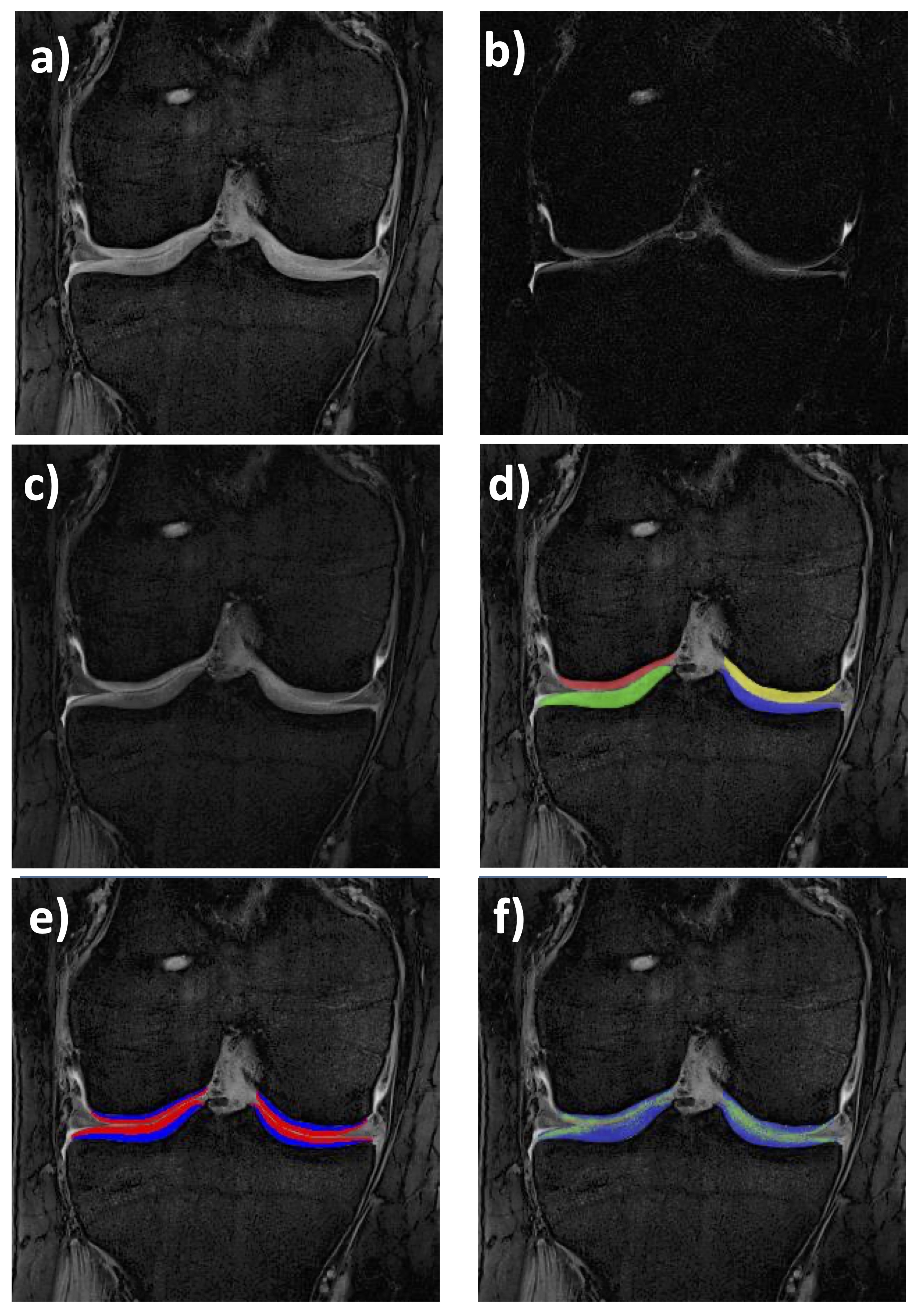

From an MR image acquisition perspective, T2 maps can be generated by various spin echo or gradient echo techniques [4]; the most widely used is 2D multiple-echo spin-echo (MESE – Fig. 1). MESE uses 4-8 different echo times (TEs) to derive T2 on a voxel-by-voxel basis. Yet a more versatile 3D gradient echo-based sequence has recently been proposed, i.e. quantitative double echo at steady state (qDESS – Fig. 2) in combination with water excitation [23–28]. qDESS generates two echoes per repetition time (Fig. 2), separated by a spoiler gradient. An image is formed from each echo, and T2 can then be computed from changes in voxel signal intensity between the two sets of images. The image formed from the first echo displays mixed T1/T2 contrast, whereas the image formed from the second echo exhibits contrast with contributions from both T2 and diffusion effects. Conventional DESS[24, 29, 30] combines data from both echoes (Figs 2 a, b) to generate a single (fused) image with mixed T1-/T2-contrast (Fig. 2c), enabling morphometry but not relaxometry (T2). However, with a modification of the gradient fields and images from both echoes stored separately (qDESS), a voxel-by-voxel fit can generate the desired high-resolution T2 map (Fig. 2f). This approach has been validated versus single echo spin echo T2, the gold standard for this type of measurement [23–27].

Other important contrast mechanisms in compositional cartilage imaging are those to estimate proteoglycan (or glycosaminoglycan) content in the cartilage, both being strongly negatively charged [31–33]. Probably the most known is Delayed Gadolinium-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Cartilage (dGEMRIC)[31–33], determining the “delayed” uptake of negatively charged gadolinium at some time after intravenous injection. This uptake is greater in regions of proteoglycan depletion owing to the reduced negative fixed charge density from the proteoglycans in these regions. However, de to the complexity of the injection, the delayed image acquisition, and the relatively long acquisition time, it has not been commonly used in clinical trials. Further techniques quantitatively probe spin–lattice relaxation in the rotating frame (T1rho), a type of spin-lattice relaxation achieved by using a so-called “spin-locking” pulse that effectively locks the magnetization into a rotating frame [4]. The T1rho decay time is sensitive to interactions between water- and macro-molecules of the cartilage matrix, and thus can be used to assess proteoglycan content in cartilage. Glycosaminoglycan Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (gagCEST)[34] uses chemical exchange between glycosaminoglycans and water protons to enhance the imaging signal, whereas sodium MRI (Na-23 MRI)[35] directly measures the content of the (positively charged) sodium cation (rather than hydrogen) in the extracellular matrix, which is positively correlated with the concentration of the negatively charged glycosaminoglycans. Common to all these methods is that they have not been used in clinical trials, since (with the exception of dGEMRIC) they require high field scanners, dedicated radiofrequency hardware (coils), and sequences that are not readily available outside a few academic centers.

The objective of this selfie review is to summarize recent progress made by our work groups in imaging cartilage T2 in the knee, with most of the work focusing on the femorotibial joint. It expands from initial method development and technical implementations, supported by the Paracelsus Medical University Research Fund (PMU FFF), to its application in large clinical cohorts and trials, which has been supported by national and international funding bodies, including the EU. The purpose is on vertical integration of our own work by history and content rather than the horizonal integration with other (T2) literature, since this approach can be found in the discussion section of each of the papers and abstracts cited.

Other important contrast mechanisms in compositional cartilage imaging are those to estimate proteoglycan (or glycosaminoglycan) content in the cartilage, both being strongly negatively charged [31–33]. Probably the most known is Delayed Gadolinium-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Cartilage (dGEMRIC)[31–33], determining the “delayed” uptake of negatively charged gadolinium at some time after intravenous injection. This uptake is greater in regions of proteoglycan depletion owing to the reduced negative fixed charge density from the proteoglycans in these regions. However, de to the complexity of the injection, the delayed image acquisition, and the relatively long acquisition time, it has not been commonly used in clinical trials. Further techniques quantitatively probe spin–lattice relaxation in the rotating frame (T1rho), a type of spin-lattice relaxation achieved by using a so-called “spin-locking” pulse that effectively locks the magnetization into a rotating frame [4]. The T1rho decay time is sensitive to interactions between water- and macro-molecules of the cartilage matrix, and thus can be used to assess proteoglycan content in cartilage. Glycosaminoglycan Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (gagCEST)[34] uses chemical exchange between glycosaminoglycans and water protons to enhance the imaging signal, whereas sodium MRI (Na-23 MRI)[35] directly measures the content of the (positively charged) sodium cation (rather than hydrogen) in the extracellular matrix, which is positively correlated with the concentration of the negatively charged glycosaminoglycans. Common to all these methods is that they have not been used in clinical trials, since (with the exception of dGEMRIC) they require high field scanners, dedicated radiofrequency hardware (coils), and sequences that are not readily available outside a few academic centers.

The objective of this selfie review is to summarize recent progress made by our work groups in imaging cartilage T2 in the knee, with most of the work focusing on the femorotibial joint. It expands from initial method development and technical implementations, supported by the Paracelsus Medical University Research Fund (PMU FFF), to its application in large clinical cohorts and trials, which has been supported by national and international funding bodies, including the EU. The purpose is on vertical integration of our own work by history and content rather than the horizonal integration with other (T2) literature, since this approach can be found in the discussion section of each of the papers and abstracts cited.

Figure 2. Coronal quantitative double-echo steady-state (qDESS) MRI of the femorotibial joint (FTJ): a) First echo (4.85 ms); b) Second echo (12.14 ms); c) Merged qDESS image (a and b) with mixed contrast; d) Cartilage segmentation of the medial (MT) & lateral tibia (LT), and medial (cMF) & lateral femur (cLF); e) Cartilage segmentations of the four FTJ plates showing the superficial & deep layer (50% of the total local thickness, respectively); f)T2 map (only cartilage T2 is shown, no other structures)

Original articles and conference abstracts on knee (mostly femorotibial) cartilage T2 published by our group (“selfie” approach) were included and reviewed, categorizing each by the relevant funding source, providing the type of publication (full paper or abstract), MRI field strength, observation span (baseline only, or longitudinal), and segmentation type (manual or automated), and summarizing the key findings in a coherent manner. These were linked to the history of the compositional and specifically T2 analysis field and to work by other groups on this or related areas, where deemed useful and where providing important context

Childhood: The Early Days of Laminar T2-Funding (PMU FFF and Nana DiaRa)The NanoDiaRa project (2010–2014) aimed at developing superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) as diagnostic tools for early detection of rheumatoid arthritis and OA, funded by the EU Commission's 7th Framework Program (F1 - Table 1; NanoDiaRa). As a project partner, we started to apply the cartilage morphology measurement technology established in our group to the analysis of cartilage T2. While much of the work was focused on analyzing cartilage thickness change in a randomized control trial (RCT) on the efficacy of anterior cruciate ligament repair (ACLR) after injury vs. state-of-the-art physical therapy (the KANON study)[36, 37], one of the NanaDiaRa partners (Table 1) provided a posterior cruciate ligament repair (PCLR) cohort as well as young and more mature professional volleyball athletes (Supplemental Table 1). These were not only studied using MRI sequences for cartilage thickness (change)[38], but also for T2, using an MESE protocol. Interestingly, the young athletes displayed a significant increase in cartilage thickness in the young (towards the end of adolescence), whereas the mature athletes showed high rates of (lateral) femorotibial cartilage loss (31). Exploring concomitant compositional (T2) changes [39] revealed that, in adolescents, a longitudinal decrease in T2 was observed in the deep cartilage layers of the medial femorotibial compartment, without a significant change in the superficial layers, and without any change in laminar T2 of mature athletes [39]. This first pilot study on qMRI relaxometry of cartilage maturation was suggestive of organizational changes occurring in the deep (radial and transitional) layer of the collagen matrix at the end of adolescence, and highlights the necessity to separate the deep and superficial cartilage laminae (here 50/50) to elucidate relevant processes in this highly heterogeneous and anisotropic tissue [39].

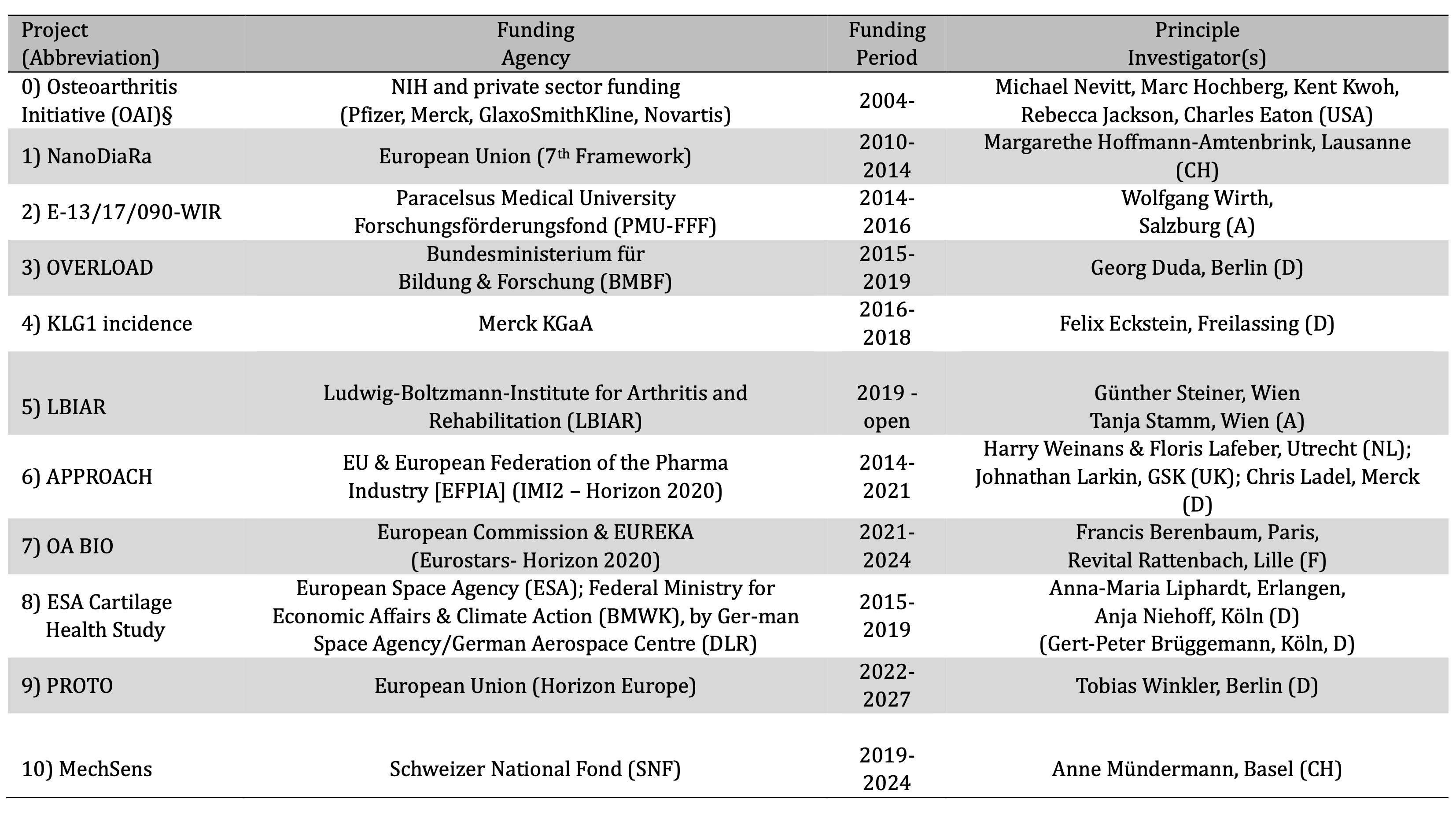

Table 1. Grants obtained by our group that funded the T2-projects summarized in this selfie review. § has funded image acquisition and availability as an publicly accessible image repository, but not image analysis; NIH = National Institute of Health (USA); NanoDiaRa = Development of Novel Nanotechnology Based Diagnostic Systems for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis; KLG = Kellgren Lawrence Grade; APPROACH = Applied Public-Private Research enabling OsteoArthritis Clinical Headway; PROTO = Advanced PeRsOnalized Theapies for Ostearthritis;

Country abbreviations: USA = United States of America; CH = Switzerland; A = Austria; D = Germany; NL = The Netherlands; UK = United Kingdom; F = France

Based on these initial findings, seed funding was obtained from the PMU FFF(F2 - Table 1; PMU FFF) to improve the usefulness and versatility in the technical implementation of the T2 analysis, by adding tools for measuring (up to 16) defined femorotibial subregions [40]. Further, the grant funded the application of such cartilage T2 relaxometry to explore some clinically relevant research questions. A series of three studies examined differences of subregional (laminar) cartilage T2 by age and sex in healthy subjects [41], between healthy and early OA samples [42], and between OA knees with and without substantial subsequent progression [43]. In almost 100 healthy subjects (age 45-78), cartilage T2 of the deep and superficial femorotibial cartilage was measured in the 16 defined femorotibial subregions (Fig. 1), using the MESE sequence [21, 29, 44]. Significant variation in femorotibial cartilage T2 between subregions was observed in both the superficial and deep cartilage layers, but no differences were observed between male or female cartilage, and between those below and above the median age (54y)[41]. This first study to report subregional (layer-specific) compositional variation of femorotibial cartilage T2 in healthy adults hence identifies significant differences in the superficial and deep cartilage T2 between femorotibial subregions; yet no relevant sex- or age-dependence of cartilage T2 was observed between age 45-78 years [41]. This suggests that common layer- and region-specific T2 reference values can be used to identify compositional pathology in joint disease across both sexes and for all age groups captured in the above range [41]. Exploring early OA (definite osteophytes on radiographs, but no radiographic joint space narrowing) and knees at risk (relevant factors of incident OA), we found no significant difference between those in either cartilage layer [42]. However, both those at risk and those with early (radiographic) OA displayed significantly longer cartilage T2 in the deep and superficial layers [42] than those in the healthy reference cohort [41]. We further studied laminar T2 subjects with medial femorotibial progression by both cartilage loss from quantitative MRI, and by joint space width (JSW) loss for semi-flexed weight-bearing radiographs in comparison with knees matched by sex, body mass index, baseline Kellgren-Lawrence-grade (KLG), and pain that did not display progression with either method anywhere in the joint [43]. At baseline, no statistically significant difference in deep or superficial cartilage T2 was observed between both groups, but the 1-year increase in deep (not superficial!) medial T2 that occurred concurrently was more pronounced in the progressor than in the non-progressor knees [43]. Thus, T2 did not appear to be a strong prognostic factor for subsequent structural progression in the same compartment of knees with established radiographic OA, when appropriately controlling for covariates, but deep cartilage longitudinal T2 change occurred concurrent with progression. The implementation of the subregional analysis approach was then used to examine the diagnostic performance of T2 across various pre-radiographic and radiographic OA strata [45]. Interestingly, peripheral (rather than central) subregions and superficial (rather than deep) cartilage T2 more efficiently differentiated various pre-radiographic OA stages. The hypothesis that the ratio of superficial vs. deep layer T2 or central vs. peripheral T2 can enhance diagnostic performance had to be refuted [46]. As previously done with cartilage thickness [47], the subregion approach was expanded to a location-independent analysis technique of cartilage T2 across the femorotibial joint. This method permits one to retrieve T2 times that express a weighted summary of the magnitude of the regional values (or longitudinal changes over time), independent of where they occur in the joint [48–50]. A cross sectional application revealed that location-independent laminar cartilage T2 analysis is equally sensitive to differences between healthy knees vs. those with radiographic OA as is subregional analysis [50]. Further, the method efficiently differentiated knees at various stages of radiographic OA, with the advantage that it does not rely on any “a priori” assumption about locations where the strongest differences may be observed [50]. Finally, no statistical penalty needs to be applied to account for performing parallel statistical tests for multiple endpoints. When applied longitudinally to the determination of T2 lengthening and shortening scores across the femorotibial joint [49], ordered values (of subregional T2 change over one year) revealed significant differences in both the superficial and deep cartilage layer between radiographic strata, whereas the region-specific T2 measures were insensitive to such differences in longitudinal change [48].

When applying these developments within the NanoDiaRa project data, exploration in the femoro-patellar compartment (patellar and trochlear cartilage) did not identify significant sex-differences in cartilage T2 (or its change) in the adolescent athletes, while mature males exhibited significantly greater longitudinal T2 lengthening than their female counterparts [51]. This was likely associated with the occurrence of femoropatellar cartilage loss that was more than twice greater in men than in women [51], particularly since a significant relationship between a T2 increase and cartilage thickness loss was previously demonstrated also in the femorotibial joint [43]. In another NanoDiaRa study (Table 1), we aimed to determine longitudinal changes in knee cartilage morphology (thickness) and composition (T2) after posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) rupture and reconstruction (PCLR)[52], and to compare these to uninjured controls (the above mature athletes)[38, 51]. Adults with PCLR for isolated and multi-ligament injury had MRIs acquired at > 5 years post-PCLR with 1 year follow-up [52]. Location-specific changes in knee cartilage thickness and T2 were determined quantitatively and compared with the controls. The annual cartilage thickness loss was greatest in the medial femorotibial compartment, and in the medial femoral condyle and trochlea the PCLR cases lost significantly more cartilage thickness over time than uninjured controls [52]. Surprisingly, the deep and superficial T2 values were relatively stable over time, without differences between the PCLR and control knees [52], but with 15 cases and 13 controls the study was not well powered.

Growing up: The OVERLOAD (BMBF) OA Project

A subsequent set of laminar T2 studies was conducted as part of the OVERLOAD project that was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) together with PrevOP, with project leads located in Berlin. As is the intention of the BMBF, this collaborative interdisciplinary research initiative included a number of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and used a holistic approach to combating this complex disease. It set the focus on the prevention and treatment of OA, specifically on developing an understanding of how mechanical factors cause disease progression. Most of our (initial) T2 work on this study relied on data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI - NCT00080171). The OAI is a publicly accessible image (and clinical data) repository that included MESE MRI acquisitions for the determination of T2 in almost 5000 participants [21, 29, 44]. It represents a multi-center, longitudinal, observational study that aims at identifying (imaging) biomarkers and risk factors for the development and progression of knee OA, with radiographs and 3T MRIs taken annually between baseline and 4y follow-up at four sites [21, 29, 44]. The imaging data are publicly available and widely used in the research community to explore OA pathophysiology, to develop and validate novel semi-quantitative and fully quantitative imaging biomarkers, and (more recently) to develop fully automated segmentation methodologies using artificial intelligence, deep learning, and specifically convolutional neural network-based algorithms [24, 53–56]. The high consistency, quality, and longitudinal nature of the images make the OAI an invaluable resource for studying disease incidence and progression, and the relationship of imaging biomarkers with clinical outcomes [57–60].

A series of studies was conducted using this unique data set. Radiographically normal knees (KLG0) “at risk” of incident OA displayed greater (location-independent) cartilage thickening than “non-exposed” healthy OAI knees, whereas superficial or deep cartilage T2 change over 3 years did not differ significantly between both groups [61]. The “at risk” group was defined by obesity, previous knee trauma or surgery, family history of total knee replacement, presence of Heberden's nodes, engagement in at least one frequent repetitive knee activity, or knee pain. Those from the “non-exposed” cohort were aged 45–79 and were without such risk factors and without pain, aching, stiffness or radiographic changes in either knee [61]. However, using an “early” OA model [62], we found that radiographically normal knees with moderate to severe radiographic changes (joint space narrowing) in the contralateral knee display a significantly greater longitudinal 3-year increase in deep femorotibial cartilage T2 than those with radiographically normal contralateral knees, and a greater superficial medial T2 at baseline [49]. Location-independent analysis (determining T2 shortening and lengthening scores) confirmed the longitudinal findings [49]. Yet baseline structural pathologies (defined by semi-quantitative MRI observations) were not significantly associated with the longitudinal change in femorotibial T2 in knees without radiographic OA[63]. Following an inverse approach, we studied whether laminar T2 was associated with the incidence and worsening structural pathology [64]. In knees with incident or worsening cartilage lesions, baseline deep layer T2 was observed to be greater than in those without, whereas in those with incident or worsening BMLs, superficial T2 was elevated in some femorotibial plates. This finding was contrary to the expectation that superficial T2 would be more strongly related to cartilage lesions, and deep T2 to that of bone marrow lesions [64].

Adolescence: More OA Initiative Applications (Merck KGaA and LBIAR)

One further application of T2 exploration using OAI data was supported by a grant from Merck KGaA, investigating pre-radiographic (KLG 1) knees, as these were considered to be under-investigated at the time. These knees had minimal or doubtful osteophytes that are generally not yet considered to be osteoarthritic. We looked at incident structural knee OA, defined in a relatively conservative manner by incident joint space narrowing (JSN) on weight-bearing radiographs over 4 years [65]. Baseline cartilage T2 was not found to be associated with subsequent radiographic progression from KLG1 to presence of JSN, but progression was accompanied by a concurrent increase in both superficial and deep cartilage T2. Hence, T2 did not appear to be a predictive (but concurrent) biomarker of incident radiographic OA at this particular transitional phase of (pre-radiographic) OA [65].

Expanding on this, and with a long-term funding scheme provided by the Austria-wide Ludwig Boltzmann Institute (cluster) of Arthritis and Rehabilitation (LBIAR), we established a technique for determining cartilage T2 in MESE MRIs of the OAI, by the registration of segmentation masks obtained from a high-resolution gradient echo double echo steady state (DESS) sequence [66]. We observed that the DESS segmentation masks (validated for cartilage thickness segmentation) did not fit the MESE cartilage images well. To match the analyses commonly done by expert readers, the DESS segmentations had to be registered at the level of the cartilage surfaces, with about 10-30% having to be “trimmed” in the depth of the cartilage layers [66]. Hence, MESE-derived T2 “misses” a substantial part of the deep cartilage layer, whereas what is considered “deep” layer in MESE is more oriented towards the intermediate cartilage layer, where the collagen fibrils are not oriented perpendicular to the subchondral calcified layer but in random order [8, 9]. In a thorough follow-up analysis, these geometric deviations between MESE and DESS were explored in more detail, and were shown to affect cartilage volume, surface areas, and thickness, and to yield greater differences in the femur than tibia (55). Applying this technique, we analyzed a set of >300 (right) knees OA knees (KLG 1-3) at two time points (baseline and 12 months follow-up), i.e. >600 MESE MRIs from The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) Biomarker Consortium set, without the requirement of direct segmentation of the MESE[68]. The FNIH (I) study cohort was selected from the OAI in order to examine risk factors and predictors of medial radiographic and clinical disease progression in those with established radiographic baseline OA[69–72]. We found the baseline superficial (but not deep) medial femorotibial T2 to be significantly elevated in full (radiographic and pain) progressor knees and in knees with joint space width (JSW) progression only, when being compared with non-progressor or “pain only” progressor knees [68]. This difference was maintained after adjustment for age, sex, body mass index, WOMAC pain, and medial joint space narrowing grade (analysis of covariance); yet 12-month change in deep or superficial T2 was not significantly associated with case status. These findings are opposite to those mentioned earlier in pre-radiographic (KLG1) knees, where baseline T2 was not predictive, but concurrent change in (deep and superficial T2) occurred with incident radiographic OA [65]. Differences may be due to the presence of established baseline radiographic OA in the latter [68] compared with the earlier [65] study.

Reading Maturity with an EU-based cohort: IMI APPROACH (EU)

The next set of T2 investigations was performed in the IMI-Approach Cohort [73]. APPROACH (Applied Public-Private Research Enabling OA Clinical Headway - NCT03883568) was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), a European collaborative project eventually aimed at improving the success rates of OA clinical trials, by identifying and validating specific patient subtypes using clinical, biomechanical, biochemical and imaging biomarkers [74, 75]. Acknowledging a great deal of heterogeneity of the disease, the study collected data from over 10, 000 OA patients, to employ a bioinformatics and machine learning approach for identifying distinct endotypes [76]. The study used machine learning models in an attempt to optimize patient recruitment strategies for clinical trials, enriching pain and radiographic progression rates by using demographic, pain, and radiographic pre-baseline information. It eventually selected almost 300 participants that were followed longitudinally over 2 years at 5 centers [73], including T2 mapping (by MESE) of femorotibial cartilage over the first 6 months. In a first study, we examined potential cartilage T2 (and thickness) differences between the participating sites, as well as the baseline test-retest reliability for those measures [77]. To that end, 3 volunteers had both knees imaged at 4 of the 5 sites (2x 1.5T and 2x 3.0T, respectively), and at the time of abstract publication, 13 patients (of 30) at 3 (of 5) sites also had completed test-retest acquisitions. Whereas the inter-site variability for cartilage thickness was only marginally greater than the test-retest errors, the between-site T2 deviations were larger than test-retest variability, larger than those between individual knees, and larger than those for cartilage thickness; systematic differences also were apparent between the two (1.5T and 3.0T) field strengths [77]. However, within a site, test-retest errors of superficial and deep cartilage T2 were small and only marginally greater than those observed for cartilage thickness [77]. To elucidate whether laminar cartilage T2 is predictive of progression, we classified knees as having significant cartilage loss (> smallest detectable change [73]) in the medial or lateral compartment. Superficial and deep layer T2 were measured at 4 (of the 5) centers using the central 3 slices in both compartments [78]. A 6-month decrease in medial deep layer T2 was associated with medial 2-year progression, but no other (significant) association was observed for changes in deep or superficial layer T2 [78]. For comparison, baseline radiographic (KLG and JSN) and MRI structural pathology (MOAKS) scores were strongly associated with medial and lateral longitudinal progression over 6, 12, and 24 months. A lower machine-learning-predicted structural progression probability was associated only with medial progression over the initial 6 months, but not with longer periods or with lateral progression. In a recent study from the IMI-APPROACH cohort, Bax et al. [79] examined the association between knee cartilage T2 and lower limb alignment (varus/valgus). They focused on 156 participants with 3.0T MESE MRI, and observed significantly longer medial and lateral T2 in KLG 2-4 than KLG 0-1 patients in the deep layer. However, only weak (although partially statistically significant) correlations were detected between T2 and alignment [79].

Reaching young adulthood: OA BIO (EUROSTARS - Horizon 2020 Framework Program)

Another major step in progressing compositional MR imaging through T2 was made by the OA-BIO European Consortium project, led by the company 4Moving Biotech, Chondrometrics GmbH, and two academic institutions. The Consortium was awarded a Eurostars grant that was part of the EU Horizon 2020 Framework Program, with the aim of developing life-changing therapy for OA patients through an (imaging) biomarkers-driven approach. Specific goals were to complete early clinical development (Phase I) of 4P-004 (i.a. Liraglutide), a first-in-class DMOAD, and to identify and validate OA imaging and liquid biopsy biomarkers. The project set out on the notion that the pressing need to bring novel DMOAD to patients is made even more challenging by the lack of clinical specific disease biomarkers.

In a first study for which funding of the EUROSTARS project was used, we compared the laminar T2 by quality-controlled expert manual segmentation of standard MESE images that were obtained at the University of Erlangen (Germany). The rationale for this study was that 0.55T MRI is potentially more widely accessible than higher field strengths and easier to use in an outpatient setting. However, such low field strength comes with lower signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) and longer acquisition times than standard systems (1.5/3T). 7T MRI, on the other hand, is available in some hospitals, but access is still very limited. Further, as different magnets are commonly used in multicenter clinical trials, we aimed to compare the agreement and precision of laminar femorotibial cartilage T2 across different field strengths. 12 volunteers were imaged on four systems (Siemens Healthineers: Magnetom Free Max (0.55T), Sola (1.5T), Vida (3T), and Terra (7T). Six participants had repeat acquisitions, with repositioning of the knee between test and retest. The superficial and deep femorotibial cartilage T2 both differed significantly between field strengths; they were shortest at 7.0 and longest at 0.55T (Δ ~ 10ms). Interestingly, the ratio of superficial vs. deep cartilage T2 was relatively constant across the different field strengths (Δ ~ 10ms). Test-retest precision was similar for superficial and deep cartilage, highest at 3.0T (approx. 1.1%) and lowest at 0.55T (approx. 3.6%). As for our previous study including 1.5 and 3.0T [77]; these findings suggested that cartilage T2 has to be interpreted with care when generated from different systems at different field strengths, particularly when being pooled in multicenter studies, particularly for cross-sectional analysis. In such cases, correction factors may be required to harmonize the data. At this point, T2-analysis from 7T machines calls for further optimization, to leverage the potential benefit of higher field strengths, and T2 analysis at 3T is currently recommended for clinical trials.

An important aspect of the imaging biomarker part of the EUROSTARS project was the automation of the segmentation process to be able to scale the technology to higher demands from clinical trials and potentially clinical practice. In a pilot study, we probed whether the registration of segmentation masks from cartilage morphometry sequences (e.g. DESS)[66] or direct automated segmentation was the best path forward [80]. A preliminary comparison suggested that direct segmentation was preferable, because it proves to be more accurate when being compared with manual segmentation as a gold standard [80], and because morphometric segmentations are not always available for cohorts of interest.

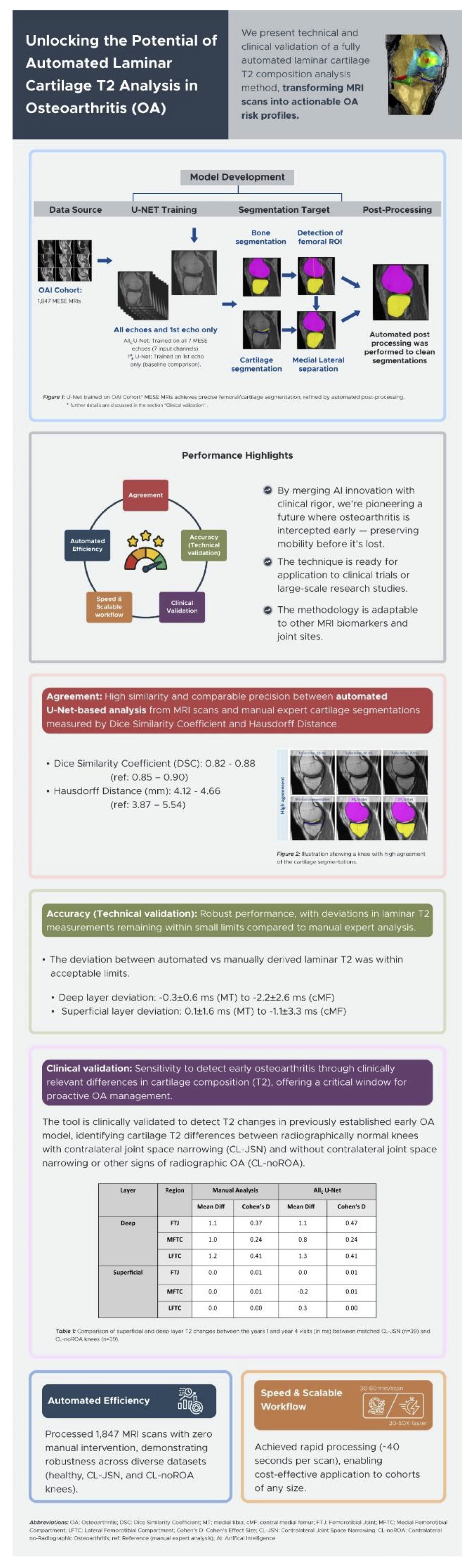

In a first larger study of automated T2 implementation using convolutional neural networks (CNNs, an AI-based deep learning method), we aimed at technically and clinically validating the approach by comparing radiographically normal knees with vs. without contra-lateral joint space narrowing (JSN)[81], with an Infographic being displayed in Fig. 3. 2D U-Nets (an implementation of CNN-based segmentation) were trained from manually segmented femorotibial cartilage from MESE MRIs obtained by the OAI[81]. There was good agreement (Dice Similarity Coefficients [DSCs] >0.82) between automated and manual expert segmentation, and deviation between both approaches for laminar T2 were small (-2.2 to +4.1ms). The automated approach had similar sensitivity to the baseline T2 differences between the two groups of radiographically normal knees (i.e. in the superficial layer), and similar between-group longitudinal performance over 3y compared with manual analysis, with differences noticeable in the deep layer (65). Next, we compared the automated vs. manual segmentation pipeline for determining differences in laminar cartilage T2 in radiographically normal (KLG0) knees with and without MRI OA Knee Score (MOAKS) cartilage damage present, again using MESE MRI from the OAI [82]. Automated bone segmentation was used to determine a) the weight-bearing femoral region of interest on the sagittal images, and b) to select the MRI slices requiring cartilage segmentation. Automated post-processing was used to identify and correct implausible segmentations [82]. Of 741 knees studied, 408 did not have cartilage damage, 115 had medial, 149 had lateral, and 69 had both medial and lateral MOAKS cartilage damage. In the medial compartment, superficial (but not deep) T2 was prolonged in knees with cartilage damage vs. those without, both for manual and automated segmentation [82]. Laterally T2 was longer in both laminae of MOAKS damage knees, both for manual and automated analysis, with similar effect sizes. Hence, this second clinical model confirmed that the fully automated U-Net-based cartilage segmentation pipeline was as sensitive to differences in laminar cartilage T2 between knees with vs. without cartilage damage, as is quality-controlled, manual cartilage segmentations [82].

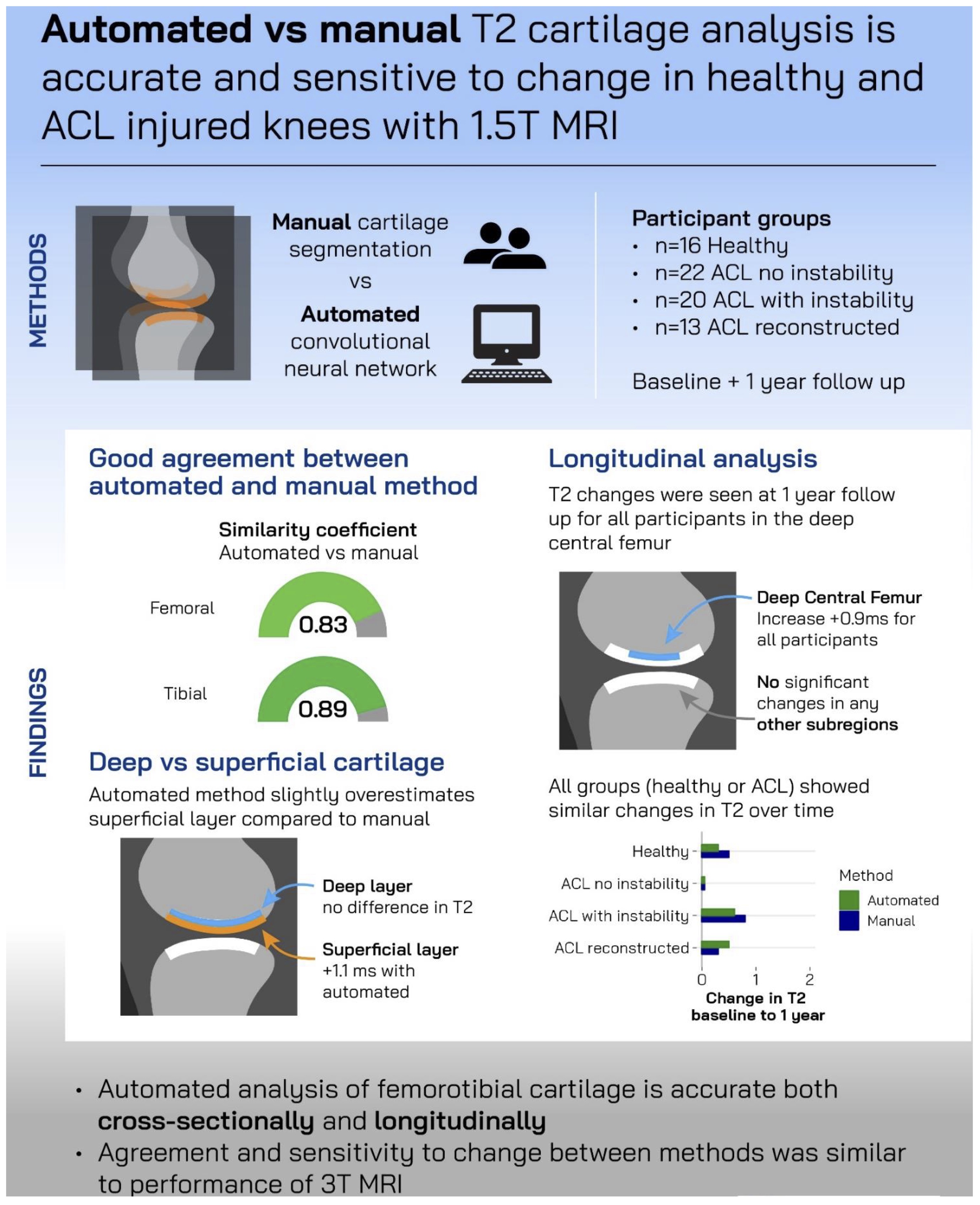

Figure 3. Infographic visualizing major findings of Wirth et al. [81]; created by Samra Sardar, PharmaTech Consult ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark

Middle Adulthood: Cartilage T2 in post-traumatic (OVERLOAD) and micro-gravity models (ESA)

Since cartilage T2 represents a marker of early disease, its application is naturally of particular interest in monitoring knees post injury or surgery, i.e. with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) pathology, to track potential development of post-traumatic OA (PT-OA). We presented an application in posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) pathology earlier in this article [52], but PCL conditions are clinically much less frequent than ACL injury. Another interesting application is that of examining the effect of immobilization or microgravity conditions, for instance to determine the amount of countermeasures required to maintain cartilage health. This is because findings from bed-rest studies and other spaceflight analog model research suggest that offloading is associated with marked alterations in cartilage metabolism [83]

In this context, we studied ACL-injured knees from the OVERLOAD study, with the cartilage thickness analysis funded through the BMBF, and the T2 analysis through EUROSTARS. This provided us with another opportunity to compare automated MESE-based T2 with manual analysis, but with 1.5T data (from Charite in Berlin – Fig. 1) rather than 3.0T data from the OAI [84]. As in the two previous clinical validation studies, segmentation agreement (measured by DSCs) was high, and so was the accuracy of determining laminar T2 by comparing it between automated and manual segmentation in the deep and superficial layers [84]. An infographic of the main findings is shown in Fig. 4. Surprisingly though, at the time-point of the MRI examination on average approximately 18 weeks after the injury, no significant cross sectional T2 difference in either lamina were identified between the following subgroups of participants: a) without surgery and with biomechanically measured instability, b) without surgery and without such instability, c) with ACL repair surgery, and d) without ACL pathology (healthy volunteers) (78). This was the case for automated and for manual analysis alike, and the same applied to longitudinal T2 observations, for which no difference was observed between the four groups. As a matter of fact, no relevant longitudinal change was noted over a 1-year follow-up period in most regions, with exception of the deep lamina of the lateral femorotibial compartment. There, a significant longitudinal increase in T2 was noted in all the above groups, both with automated and with manual analysis [84]. Similarly, no relevant differences in cartilage T2 were noted in the post-ACL-injury cohort between those treated conservatively with intense structured physical rehabilitation vs. those who followed a course of regular (German) standard of care post ACL injury [85].

In the European Space Agency (ESA) cartilage healthy study, for which we receive support for cartilage T2 analysis from the ESA, we observed an effect of microgravity during longer duration spaceflight on femorotibial cartilage T2 as derived from 3T MESE [86]. The knees of 12 United States Operational Segment (USOS) crew members, with a mission length of 4 to 6 months on the International Space Station (ISS), were imaged pre-flight (launch), and on three occasions after landing (return +7, +30 and +365 days). The T2 of the superficial medial tibial cartilage was significantly affected by “time points” and was increased by about 3% after landing compared with preflight values. This may reflect an increase of fluid content, indicative of tissue matrix perturbation after prolonged offloading periods in the superficial medial tibia; yet no significant effect was seen in the other cartilage plates or in the deep layer. However, the T2 results were supported by parallel urine and serum biomarker analyses that suggested a shift in the cartilage metabolism towards degradation after space flight and staying at the ISS.

Figure 4. Infographic visualizing major findings of Eckstein et al. 2024 [84]; created by Mick Girdwood, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Finally, the Golden Age? Towards fast, high-resolution T2 relaxometry (PROTO & Mechsense)

As alluded to in the introduction, a relatively novel quantitative double echo steady state (qDESS – Fig. 2) sequence with water excitation can image knee cartilage with high resolution, low acquisition time, superior contrast-to-noise, and - in contrast to MESE - without “missing” much of the radial (deepest) cartilage layer [66]. This is important, because several of the above studies have suggested that the greatest sensitivity of T2 to OA related changes is in the deep layer. Heule et al. (21) was one of the first to propose qDESS rather than MESE for T2-estimation, to enable simultaneous extraction of relaxometry and morphology cartilage measures. Please note that the benefit is not only a markedly reduced acquisition time for the comprehensive study of cartilage health, increasing the well-being and compliance of patients, but that further only a single segmentation is necessary for extracting T2 and thickness, facilitating the cartilage analysis workflow greatly and reducing time and cost required for the analysis. The above authors introduced a novel post-processing approach to overcome T1-related bias for rapid DESS-based T2 quantification in the low flip angle regime by a rough global T1 estimator and a golden section search (21). Chaudhari et al. then used qDESS and compared both the cartilage thickness and cartilage T2 (as well as meniscus T2 and MOAKS semi-quantitative scores) measures with those from gold-standard methodologies in 15 volunteers and 15 OA patients, respectively [23]. Note that the difference in imaging time between a T2-standard qDESS (0.62 mm in-plane resolution: 2:37 min) and a morphometry-standard qDESS (0.31 mm: 14:20 min) was substantial, albeit still low with the combined imaging time of a non-quantitative standard DESS for morphometry, and MESE in the OAI (21 min scan time per knee combined). Therefore, the authors optimized target sequence (qDESS-EXP) readout bandwidth (642 kHz) to reduce the readout duration, while achieving high spatial resolution. Further, the target qDESS employed a 384x512 matrix (in readout and phase-encode directions) to maintain short repetition (TR) and echo times (TE), to achieve high SNR for T2-relaxometry, and the high in-plane resolution desired for morphometry, at an acquisition time of 4:48 mins (16). Applying this sequence, test-retest precision of cartilage thickness of <1%, and that of T2 <2%, with high agreement with gold standard measurement. Using this type of qDESS, the same authors set out to demonstrate a rapid pulse sequence that can be implemented across different MRI vendors with harmonized parameters that yields highly consistent cartilage morphometry and T2 relaxometry outcomes [87]. The left and right knees of 5 participants were imaged (including test-retest) using a 3T GE Signa Premier (18 channel transmit/receive coil), and a 3T Philips Ingenia (16 channel transmit/receive coil) yet only with 3 mm slice thickness [87]. Scan-rescan repeatability was high for all metrics with a maximum variability (CV%) of 2.1% for morphometry, and 4.4% for T2 relaxometry. At inter-vendor comparison, cartilage thickness and volume variation were moderate (about 4.0%), but that for cartilage T2 was relatively high (up to 13%). Inter-vendor T2 left-right asymmetry repeatability between both knees did not differ significantly between the two vendors (p=0.11)(81).

PROTO Horizon is a project currently funded by the EU with a focus of the role of inflammation / synovitis on OA progression and therapy. As part of the project, two clinical trials are anticipated to take place, one in ACL inured patients with objective instability, randomized either to a complex 3x weekly biomechanical intervention, or to the standard of care post-surgery. The other one is a phase 2 study testing the intra-articular injection of placental cells as a disease modifying intervention. Leading WP6, our group at PMU is responsible for developing quantitative imaging biomarkers of inflammation and validating these technically and clinically in various cohorts. Further, we are to apply these as well as cartilage morphometry and T2 relaxometry to both trials. As a first step, we published a design paper describing and discussing the full image acquisition protocol of both trials, with the condition of not exceeding a total image acquisition time of 30 mins (18). Apart from standard clinical MRI sequences, qDESS (Fig. 2) represents the true “work-horse” supporting quantitative assessments in both trials, including cartilage T2 relaxometry, morphometry (with high in-plane resolution), meniscus analysis [72], and potential detection of synovitis in the Hoffa fat pad [88]. This has been expanded by a recent white paper on “multifaceted” imaging, i.e. using one imaging modality to retrieve a plethora of different image contrasts [89]. The white paper introduces the concept of a “precision and value chain” that must ensure matching the imaging protocol and clinical trial patient selection (displaying the appropriate imaging phenotype, and ideally the right endotype and theratype) to the mechanism of action of a putative disease modifying intervention (83). Further, the image analysis tools and endpoints need to be closely adapted to the protocol, and this in turn needs to support the desired analysis [89]. Given that “multifaceted” imaging produces a multitude of imaging endpoints and potential surrogate markers, concepts need to be defined “a priori” on how to deal with this multiplicity statistically, and/or how to construct clearly defined multicomponent or composite endpoints “a priori”[90].

To clinically validate qDESS for T2 relaxometry, Herger et al. analyzed data from the MechSense study by quality-controlled manual cartilage segmentation. The study included younger and older participants with an ACL-deficient knee ( 2-10y after the injury), these being compared with the contra-lateral knees and with matched healthy participants (19). ACL-deficient knees were found to display longer T2 in the deep albeit not in the superficial femorotibial cartilage layer, but similar cartilage thickness values in comparison to the contra-lateral non-injured or the healthy comparison knees (19). This was in contrast with the T2 status in the ACL-deficient knees from the Overload study [84], potentially explained by the current one being conducted at 3T (19) and the former on at 1.5T [84], and/or because qDESS captures more of the deep cartilage layer than the MESE[66]. Over a period of 2y follow-up, the ACL-knees did not show obvious further changes in T2 in comparison with contralateral or healthy knees [91].

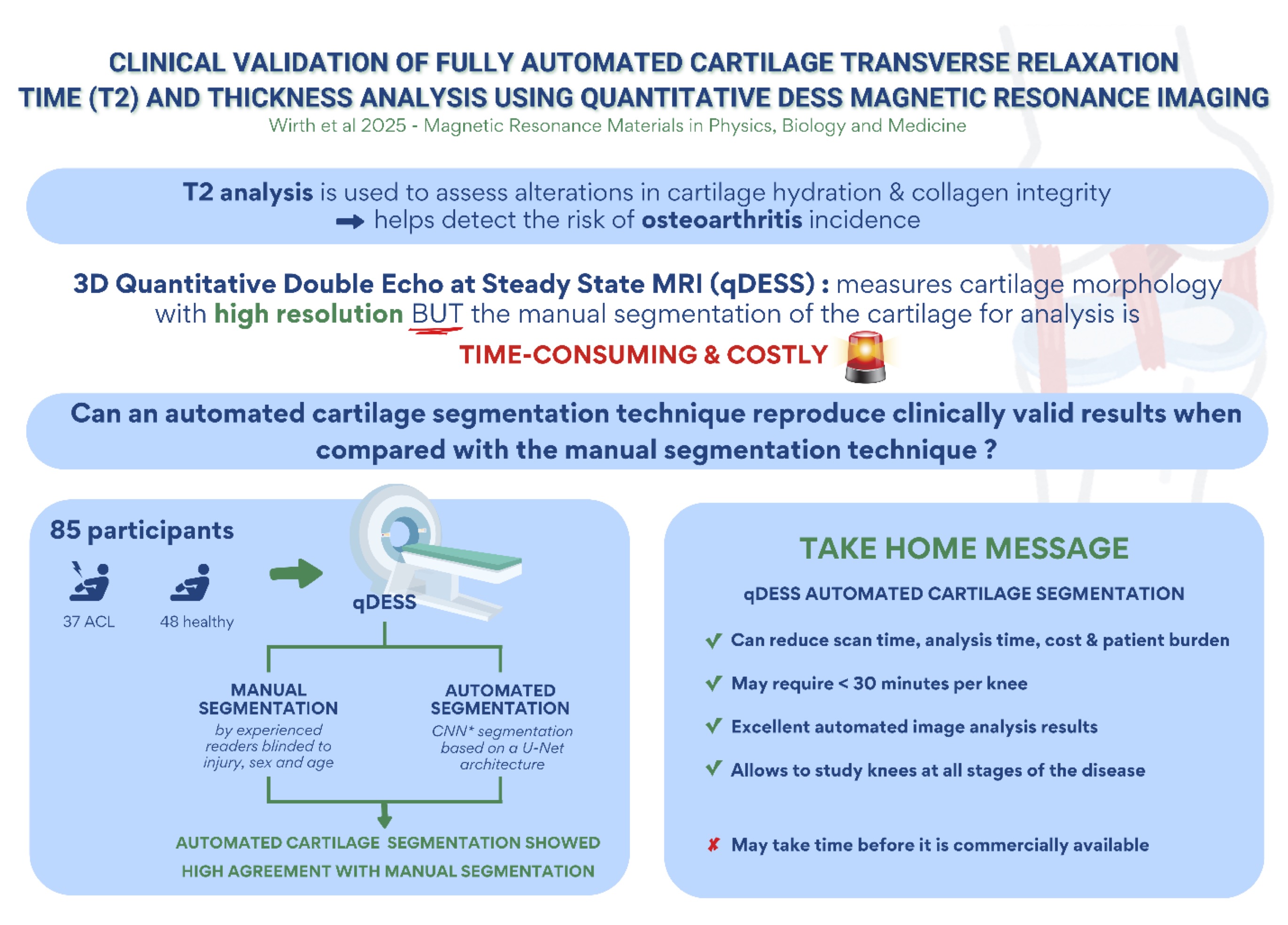

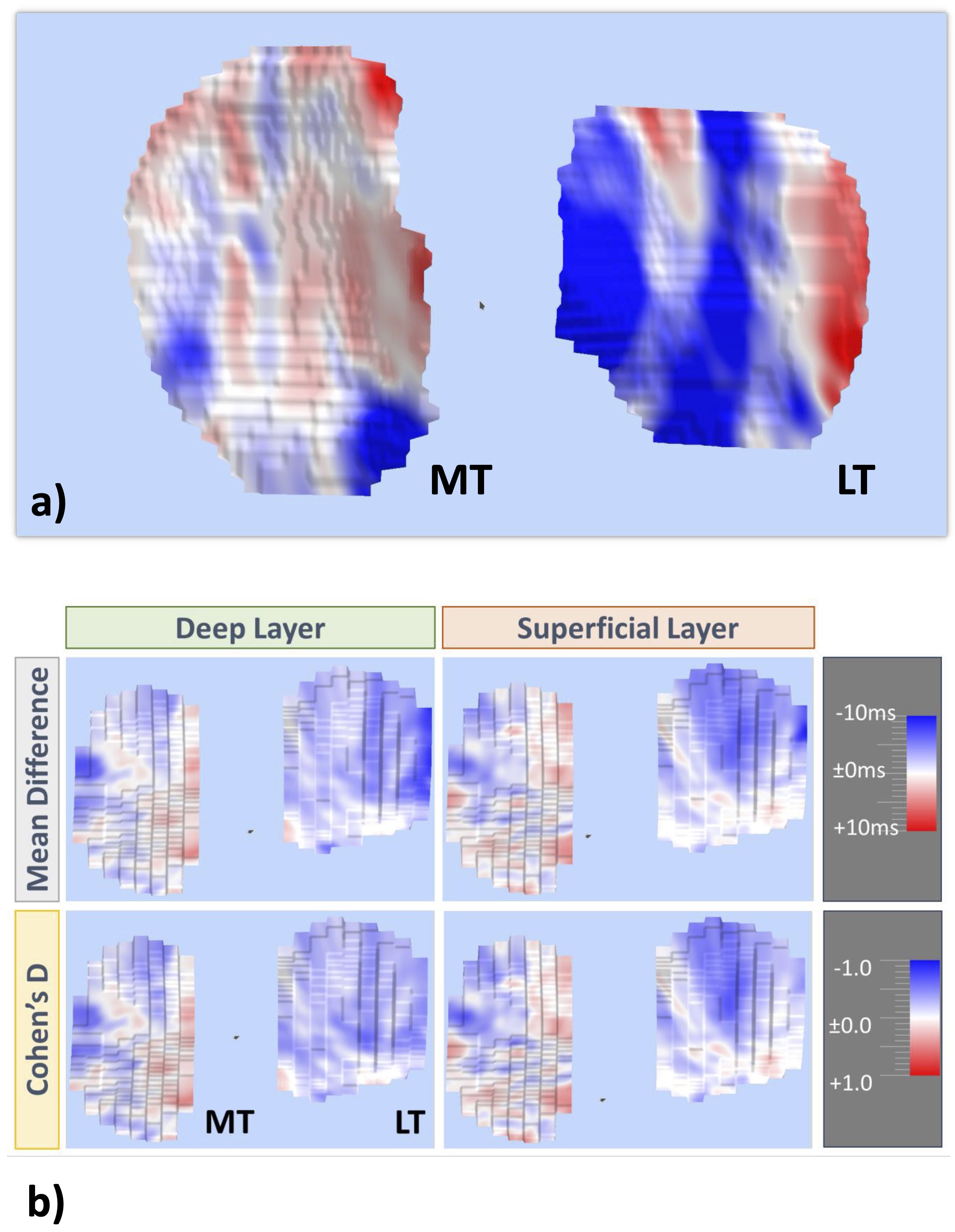

In a first paper validating fully automated T2 analysis from a qDESS MRI sequence, Wirth et al [92]. were able to reproduce the findings of the above study reporting high segmentation agreement, a high level of T2 measurement accuracy in the superficial and deep layers, and the same pattern of baseline T2 differences between ACL-deficient and contralateral or healthy knees [92]. An infographic on these findings is displayed in Fig. 5. An automated analysis of the longitudinal data (86) is currently in progress. An example of a spatial color-coded map of T2 change in the deep and superficial tibial cartilage layer, respectively, is shown in Fig. 6a. An Illustration of longitudinal T2 change in case vs. control knees visualizing the spatial pattern of the mean difference for both cohorts as well as the effect size (Cohen’s D) is displayed in Fig. 6b.

Figure 5. Infographic visualizing major findings of Wirth et al. 2025 [92]; created by Stephanie Tamer, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Figure 6. Longitudinal analysis of the spatial distribution of T2 changes across the cartilage surfaces: a) Example of a spatial color coded map of longitudinal T2 change in the deep and superficial tibial cartilage layer, respectively; b) Illustration of longitudinal T2 change in the deep and superficial layers of the medial and lateral tibia (MT/LT) in case vs. control knees visualizing the spatial pattern of the mean T2 difference for both cohorts as well as the effect size characterizing the strength of these differences (Cohen’s D)

In this “within-group” review, we have summarized original articles and conference abstracts on cartilage T2 published by our group, categorized by funding source. The work shows that over the last decade, significant improvements have been made, for instance in image acquisition, with qDESS permitting faster acquisition and higher resolution. It must be noted that at this point in time, qDESS is a research sequence and is not routinely available on clinical MRI scanners. Although it is relatively straightforward to install the sequence on most MRI magnets by application specialists, some adaptations of the code have to be made depending on the specific hardware and software version, and research agreements have to be signed with the respective vendor. This poses a logistical challenge if more than a few scanners are involved in a study, and thus represents a current roadblock for the application of qDESS in larger multicenter studies. This hurdle could be overcome if the MRI vendors were to integrate qDESS into their routine portfolio of sequences available. There is actually hope that this will happen in the intermediate future, so that application of simultaneous cartilage morphometry and relaxometry will be applicable in clinical studies.

Improvements also have been made in cartilage segmentation, with AI-based convolutional neural network (CNN) algorithm available that can robustly and comprehensively segment image repositories of knee images obtained by MESE or qDESS from large cohorts. With qDESS, the additional advantage is that the automated segmentation not only permits the measurement of cartilage T2, but cartilage morphology (thickness) in parallel, without requiring a 2nd set of segmentations (manual or automated).

There now is emerging evidence that cartilage T2 designates early structural pathology of (knee) cartilage, for instance in post-traumatic OA, prior to the loss of cartilage tissue. The review also shows that the availability of a low-to-moderate-threshold seed funding may provide an important entry point for early-stage development, helping to build internal capacity and increased competitiveness to successfully apply for external grant applications. This foundational support has contributed to improving the prospects for accessing larger-scale national and international funding opportunities, and the importance of such mechanisms cannot be overestimated, especially for young and emerging universities that seek to support their faculty by enhancing their research profile and international engagement, and hence increase the visibility and importance of their academic institution.

Further areas of interest will be disentangling cartilage thickness with layer-specific T2-change, since cartilage loss perturbates the assignment of voxels to the superficial and deep layer. If cartilage is lost superficially, the question arises whether T2 change reflects compositional change of the formerly defined superficial layer or whether former superficial voxels are located now in the deep-layer and assume lower values. Another research gap is how change in cartilage T2 is related to highly specific liquid (serum or urine) biomarkers of cartilage turnover, and to further elucidate which specific compositional changes are reflected clinically. The technique must be further validated longitudinally, in diverse patient populations of cartilage disease, best using cross-modality integration with other complimentary or synergistic compositional imaging techniques and using automated segmentation approaches. In terms of biomarker qualification, cartilage T2 (change) must be prospectively related to clinical outcome, i.e. how a patient feels, functions, and survives. Only with the latter relationship being established, T2 can be established as a “surrogate” endpoint and be used in studies seeking accelerated approval of a therapeutic agent.

The T2 story will continue, particularly with qDESS as the “powerhouse” of simultaneous cartilage morphometry and T2 relaxometry. The SCUlpTOR trial (Table 2) investigates the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells (Cymerus MSCs) for treating symptomatic tibiofemoral OA and improving knee structure (cartilage T2 and thickness) over 2y [93], with the qDESS measurements analyzed using automated CNN-based algorithms. Within the PROTO consortium, we have set up and published an optimized imaging protocol (including qDESS)[25] for a) a preventive biomechanics intervention after ACL injury, and b) for a potential disease modifying anti-inflammatory DMOAD of allogeneic placental cells (PLX-PAD; by Pluri) being injected intra-articularly (Table 2). Within MAIC4MCL (MRI analysis based on Artificial Intelligence to determine quantitative parameters of Cartilage quality and morphology for patients with rupture of Medial Collateral Ligament - a new collaborative project between the LBIAR and the Tauernklinikum in Zell am See, Austria, - the Radiology department has been equipped with qDESS to conduct an observational study on injuries of the medial collateral ligament and the medial meniscus. Further, bed-rest studies and more space flight experiments are underway to elucidate the effects of non-weight-bearing and non-gravity conditions on cartilage health (Table 2).

Within LBIAR, MESE T2 from the OAI is used to explore the effect of diabetes mellitus on cartilage composition in relation to that of cartilage thickness (Table 2). Further, numerous T2 data sets from the studies presented here will be potentially included in a very large database, to be set up by an emerging consortium under the auspices of the Innovative Health Initiative (IHI) for “bid data analytics”[94]. This project aims to identify novel endpoints, or novel combinations of endpoints, for diagnosing, predicting, preventing and/or treatment efficacy OA. It is co-funded by the EU and the European Health science industry, the core goal being to translate health research and innovation into tangible benefits for society and patients. Another emphasis is in ensuring that Europe remains at the cutting edge of sustainable, patient-centric, and interdisciplinary health research. Pending final approval of the project (87), the T2 measures will be submitted to a federated learning data base, together with a plethora of other imaging, genetic, clinical, biochemical, and biomechanical biomarkers, to further improve our current understanding and concepts of preserving and restoring joint health.

Table 2. T2-publications of our work group, with assignment to the funded project; type of publication, field strength (Tesla) and observation span (Obs) for which the study was conducted (baseline only = BL, or longitudinal = LO), segmentation type (M = manual, A = automated), and summary of key findings. $ Image analysis based on MR images obtained from the Osteoarthritis Initiative data base; Obs = observation span; BL = baseline; LO = longitudinal, MFTC = medial femorotibial compartment; TFTJ = total femorotibial joint; sf = superficial; ref = reference; ROA = radiographic osteoarthritis; OP = osteophyte; JSN = joint space narrowing; LIA = location independent analysis; diff. = difference; sign. = statistically significant; KLG = Kellgren Lawrence Grade; CL = contralateral; JSN = joint space narrowing; MOAKS = Magnetic resonance imaging knee score; MESE = multi echo spin echo; HR = high resolution; GE = General Electric company; JSW = joint space width (from weight-bearing, semiflexed radiograph), CNN = convolutional neural network (an artificial intelligence and deep-learning based architecture); rehab. = rehabilitation; MT = medial tibia

CT (Computed tomography); DESS (Double echo steady state MRI sequence); dGEMRIC (Delayed Gadolinium-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Cartilage); DMOAD (Disease modifying osteoarthritis drug); EU (European Union); gagCEST (Glycosaminoglycan chemical exchange saturation transfer); MESE (Multi echo spin echo MRI sequence); MRI (Magnetic resonance imaging); OA (Osteoarthritis); OAI (Osteoarthritis Initiative); PMU (FFF, Paracelsus Medical University Forschungsförderungsfond (Research fund)); qDESS (Quantitative DESS); qMRI (quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (relaxometry)); T1 (Longitudinal (spin–lattice) relaxation time); T1 (rho, Spin–lattice relaxation in the rotating frame); T2 (Transverse (spin–spin) relaxation time);

We would like thank the funding bodies (Table 1) who have enable us to develop, explore and validate the measurement of cartilage T2 as a biomarker in (knee) osteoarthritis. Felix Eckstein’s time on conceptualizing, drafting, and finalizing the review was partly supported by PROTO Horizon and by the LBIAR. Yet, the funders did not have any direct or indirect impact on the papers selected for review and on the conclusions drawn from them.

Further, we would like to thank the first authors of the papers and abstracts cited in this review (Supplemental Table 1)

Also, we would like to thank our academic coworkers and expert readers who have provided the manual cartilage segmentations required for the T2 analyses (alphabetic order): Jana Daimer, Gudrun Goldmann, Susanne Maschek, Sabine Mühlsimer, Annette Thebis, Barbara Wehr and Anna Wisser.

We further would like to thank the principal investigators (Table 1), their teams, and the radiology centers that provided the imaging data for analysis, and most importantly the patients participating in these studies.

Author Contributions

All (three) authors defined the purpose and contributed to the design of the review. W.W. retrieved the publications and assigned each to its grants support. F.E. provided the first draft of the review. All authors edited and then approved the final version of the review, before submission.

Funding Sources

The time for conceptualizing, drafting, and finalizing this review was partially supported by PROTO – Horizon and LBIAR. The funding sources of the work cited are disclosed in the text and Table 1.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

No relevant conflict exists regarding writing this review. The funding sources who partially supported the time of the first author spent on this review did not take any influence on the selection of articles cited and how these were interpreted. Funding sources of the work presented are listed in Table 1.The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Outside this work, Felix Eckstein and Wolfgang Wirth are co-owners and employees of Chondrometrics GmbH (Ludwig-Zeller-Str. 12, 83395 Freilassing, Germany), a company providing professional image analysis service to researchers in academia and in the pharmaceutical industry. Felix Eckstein has provided or is providing consulting services to Merck KGA, Kolon TissueGene (KTG), Galapagos, Novartis, 4P Pharma/4 Motion, Trialspark/Formation Bio, Peptinov, Sanofi, and Artialis.

Neal Bangerter is a member of the Chondrometrics GmbH Scientific Advisory Board (SAB).

Disclosure of AI Assistance

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools were used in the creation of the submitted work. Specifically, ChatGPT 4.o was employed to draft paragraphs in the introduction and introductory paragraphs in the result section, which were then thoroughly reviewed and verified by all authors to ensure accuracy. None of the text written by the authors was submitted for editing by ChatGPT 4.o without final proof-reading. The methods, main results, and discussion were written without assistance of AI tools.